Introduction B

Mastering the definitions in Letter B: Concepts and Principles of the BCBA 6th Task List is essential because these foundational concepts underpin all aspects of applied behavior analysis (ABA). Here’s why it’s useful:

1. Clear Understanding of Core Concepts: Letter B covers key principles like reinforcement, punishment, and stimulus control, which form the backbone of ABA practice. A deep understanding of these principles allows you to analyze and interpret behavior accurately.

2. Effective Intervention Design: Familiarity with these definitions facilitates the design of precise, evidence-based interventions. You’ll be better equipped to choose the right strategies and adjust interventions to achieve meaningful behavior change in your clients.

3. Consistency in Practice: Mastery of these principles ensures consistency in your approach, enabling you to apply concepts across various situations and populations. This is critical for achieving predictable outcomes and maintaining a high standard of care.

4. Professional Communication: As a BCBA, you’ll need to explain ABA principles to clients, caregivers, and colleagues. A solid grasp of these definitions enables you to communicate complex ideas in a clear and accessible way, promoting collaboration and understanding.

5. Ethical and Informed Decision-Making: Understanding Letter B concepts ensures that your decisions are guided by scientifically validated principles. This leads to ethical and effective practices, helping you to make decisions that are in the best interest of the client.

6. Preparation for Advanced Skills: Mastering these foundational concepts is crucial as they serve as the building blocks for more advanced skills on the BCBA Task List. A strong grasp of Letter B allows for smoother progression into higher-level ABA strategies and techniques.

Mastering the definitions in Letter B empowers you to be a competent, ethical, and effective BCBA, capable of making informed decisions and creating positive change in the lives of individuals you work with.

B.1. Identify and distinguish among behavior, response, and response class.

1. Behavior

• Definition: Behavior is any observable and measurable action taken by an organism. In ABA, behavior refers to everything an individual does that can be seen or measured.

• Example: Walking, talking, eating, and writing are all behaviors because they are observable and measurable.

• Key Takeaway: Behavior is the overarching term that encompasses any action performed by an individual.

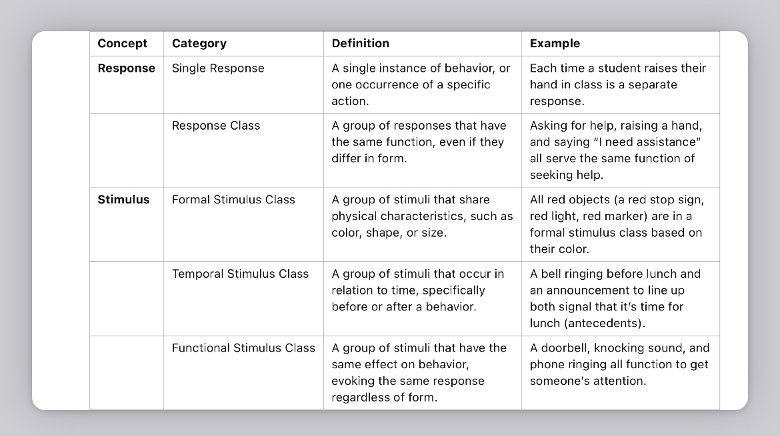

2. Response

• Definition: A response is a single instance of behavior, or one occurrence of a specific behavior.

• Example: If a person waves, each individual wave is a response. If a student raises their hand five times, each hand-raising action is a separate response.

• Key Takeaway: A response is one specific occurrence of a behavior, representing a single action or movement.

3. Response Class

• Definition: A response class is a group of responses that have the same function, meaning they achieve the same outcome or serve the same purpose, even if they look different.

• Example: A child might cry, ask for help, or gesture toward an object to get attention from an adult. These actions look different, but are all part of the same response class because they share the function of gaining attention.

• Key Takeaway: A response class groups different responses that serve the same purpose or achieve the same outcome.

Real-World Scenarios for Each Concept

1. Behavior:

• Scenario: A teacher observes a student during class to record all instances of on-task and off-task behavior, including writing, speaking, and looking around. Here, “behavior” encompasses all observable actions the student takes.

2. Response:

• Scenario: During a social skills group, a therapist encourages each child to greet their peers. Each individual “hello” or wave by each child is a response, as each one is a specific instance of greeting behavior.

3. Response Class:

• Scenario: A child in a classroom uses different ways to avoid difficult tasks, such as asking to go to the restroom, pretending to be sick, or dropping their pencil. Although the actions differ, they all belong to the same response class because they serve the function of avoiding the task.

Summary

• Behavior refers to any observable and measurable action.

• Response is a single instance or occurrence of a specific behavior.

• Response Class is a group of responses that, while different in appearance, serve the same function or achieve the same outcome.

B.2. Identify and distinguish between stimulus and stimulus class.

1. Stimulus

• Definition: A stimulus is any object, event, or condition in the environment that can affect behavior. It may be something we see, hear, touch, taste, or smell, and it can influence how we act or respond.

• Example: A teacher’s verbal instruction (“Please sit down”), a red traffic light, or the sound of a doorbell are all examples of stimuli because they can evoke specific responses.

• Key Takeaway: A stimulus is a single environmental factor that has the potential to influence behavior.

2. Stimulus Class

• Definition: A stimulus class is a group of stimuli that share common characteristics and evoke the same type of response, even if they look or sound different. They may be grouped by physical similarities, functions, or relationships to behavior. A formal stimulus class groups stimuli that share physical characteristics, such as shape, color, size, or texture.

Stimulus:

• Scenario: In a classroom, a teacher raises their hand to get students’ attention. The raised hand serves as a stimulus that prompts students to quiet down and focus on the teacher.

2. Stimulus Class:

• Scenario: A child recognizes different sounds (e.g., the school bell, the teacher clapping, or a verbal “quiet down”) as cues to pay attention to the teacher. These different sounds belong to the same functional stimulus class because they all signal to the child to quiet down and focus.

Types of Stimulus Classes:

1. Formal: Stimuli that share similar physical features (e.g., all objects that are red or all round objects).

Real World Scenario 1:

A child learns to sort toys by color. The child places all red toys (a red ball, a red car, and a red block) in one bin and all blue toys in another. Although the toys differ in form (ball, car, block), they belong to the same formal stimulus class because they share the color red. Here, the child is grouping stimuli based on their physical characteristic (color), making this a formal stimulus class.

Real World Scenario 2:

A behavior analyst is teaching a child to identify classroom expectations. They use three types of stimuli to prompt the child to be quiet.

• Formal: A red “Quiet” sign, a red stoplight symbol, and a red card each serve as a signal for the child to remain silent. These stimuli belong to a formal stimulus class because they are all red, which is associated with the “stop” or “quiet” instruction.

2. Temporal: Stimuli that occur in relation to a specific event or time (e.g., stimuli that consistently appear before a certain behavior).

Real-World Scenario 1:

Scenario: A teacher says, “Time to clean up” right before recess every day. Over time, the students begin to understand that this phrase signals the end of playtime and the beginning of clean-up. They start cleaning up whenever they hear it, anticipating the transition to recess.

Explanation: In this scenario, the teacher’s phrase “Time to clean up” consistently occurs before the behavior of cleaning up and serves as an antecedent stimulus that signals the upcoming transition. This phrase and other similar cues (like the bell ringing before recess) would form a temporal stimulus class because they occur right before the students’ clean-up behavior.

Real-World Scenario 2:

The teacher dims the lights in the classroom just before giving an instruction to quiet down. This occurs right before the behavior, acting as a temporal stimulus to prepare the students for the upcoming instruction.

3. Functional Stimulus Class

• Definition: A functional stimulus class groups stimuli that have the same effect on behavior, meaning they evoke the same response, regardless of their physical form or when they occur.

• Real-World Scenario 1:

Scenario: A young child learns to request attention in different ways, such as saying “Mommy,” tugging on their mother’s sleeve, or raising their hand. Each of these actions (saying “Mommy,” tugging, and raising a hand) results in the same outcome—gaining the mother’s attention.

Explanation: Although these behaviors differ in form, they share the same function of gaining the mother’s attention. Therefore, they form a functional stimulus class because they all serve the same purpose for the child, even though they appear different.

Real-World Scenario 2:

The teacher uses different cues to achieve the same outcome—student silence—such as saying “Quiet, please,” clapping her hands once, or ringing a small bell. All of these cues, regardless of their form, have the same function of prompting the class to quiet down, making them part of a functional stimulus class.

Real-World Scenario 3:

A child may respond similarly to different types of greetings like “Hello,” “Hi,” or a wave, which are all part of the same functional stimulus class because they serve to initiate interaction.

B.3. Identify and distinguish between respondent and operant conditioning.

1. Introduction to Learning Theories

Learning can occur in various ways, two of which are respondent conditioning (also known as classical conditioning) and operant conditioning. Understanding the difference between these two is essential in behavior analysis, as each has unique characteristics and applications.

2. Respondent Conditioning (Classical Conditioning)

WHAT IS RESPONDENT CONDITIONING? In Applied Behavior Analysis, Respondent Conditioning, also known as classical or Pavlovian conditioning, is a type of learning where a previously neutral stimulus becomes associated with an unconditioned stimulus to produce a conditioned response. This form of learning is involuntary and happens through the pairing of stimuli, rather than through consequences. In ABA therapy, respondent conditioning can help understand certain automatic responses, like anxiety or phobias. Techniques based on respondent conditioning, such as desensitization, are used to help individuals reduce or change these automatic responses to certain stimuli.

The classic example of Pavlov and his experiments with dogs provides a clear illustration of classical (or respondent) conditioning. Here’s a step-by-step explanation:

1. Background: Ivan Pavlov, a Russian physiologist, was studying digestion in dogs. During his research, he noticed that dogs would begin to salivate even before food was presented to them, just from hearing the footsteps of the lab assistant who brought the food. This observation led him to investigate further.

2. Unconditioned Stimulus (US) and Unconditioned Response (UR):

• US (Unconditioned Stimulus): Pavlov presented food to the dogs. Food naturally and automatically makes dogs salivate.

• UR (Unconditioned Response): The salivation in response to the food. This response is unlearned, meaning it is a natural reaction to the food.

3. Neutral Stimulus (NS):

• Pavlov then introduced a neutral stimulus—a bell. Initially, the sound of the bell had no effect on the dogs; it did not cause them to salivate because it was unrelated to the food.

4. Conditioning Process (Pairing the NS and US):

• Pavlov repeatedly rang the bell just before presenting the food. Over time, the dogs began to associate the sound of the bell with the upcoming food.

• Through this repeated pairing, the neutral stimulus (bell) became a conditioned stimulus (CS) because it started to produce a response when associated with food.

5. Conditioned Stimulus (CS) and Conditioned Response (CR):

• CS (Conditioned Stimulus): Eventually, the bell alone, without food, triggered salivation in the dogs. This change happened because the dogs learned to associate the bell with food.

• CR (Conditioned Response): The salivation in response to the bell alone. This response was learned (or conditioned) because it now occurred due to the association between the bell and food.

Summary of Pavlov’s Experiment:

• Before Conditioning: Food (US) naturally causes salivation (UR). The bell alone (NS) has no effect.

• During Conditioning: The bell (NS) is paired with food (US), and the dogs start to associate the two.

• After Conditioning: The bell (now a CS) alone causes salivation (now a CR), even without food.

This experiment demonstrates classical conditioning, where a neutral stimulus becomes associated with an unconditioned stimulus, leading to a conditioned response. Pavlov’s work laid the foundation for understanding how associative learning works in animals and humans alike.

• Key Concepts:

Unconditioned Stimulus (US): Naturally triggers a response (e.g., food causing salivation). This is a stimulus that naturally triggers a response without any prior learning (e.g., food causes salivation in a dog).

Unconditioned Response (UR): Automatic response to the US (e.g., salivating to food). This is the natural reaction to the unconditioned stimulus (e.g., salivating when food is present).

Neutral Stimulus (NS): Initially, this stimulus does not trigger the unconditioned response (e.g., a bell sound does not cause salivation).

Conditioning Process: By repeatedly pairing the neutral stimulus (bell) with the unconditioned stimulus (food), the neutral stimulus starts to evoke a response.

Conditioned Stimulus (CS): Initially neutral, but becomes associated with the Unconditioned Stimulus (e.g., bell sound). After repeated pairings, the previously neutral stimulus (bell) now elicits the response on its own.

Conditioned Response (CR): Learned response to the Conditioned Stimulus (e.g., salivating to the bell). This is the learned response to the conditioned stimulus (e.g., salivating when hearing the bell alone).

Real World Scenario

Respondent Conditioning (Classical Conditioning)

1. Unconditioned Stimulus (US) and Unconditioned Response (UR):

• Scenario: You smell your favorite food (US), and your mouth starts watering (UR) automatically, even before you eat anything.

2. Conditioned Stimulus (CS) and Conditioned Response (CR):

• Scenario: A child gets a vaccination (US) that causes pain (UR). After multiple visits, the child starts to feel anxious (CR) just from seeing the doctor’s white coat (CS), associating it with the pain of the shots.

3. Fear of Public Speaking:

• Scenario: During a school presentation (US), you feel nervous (UR) because of the attention. Now, when you see a stage or microphone (CS), you experience anxiety (CR) because you’ve associated these items with the discomfort of public speaking.

4. Pet Reactions to Noises:

• Scenario: You open a can of pet food (US), and your dog gets excited and salivates (UR). Over time, your dog begins to get excited (CR) just from hearing the can opener (CS) because it associates the sound with food.

5. Taste Aversion:

• Scenario: You eat a particular type of food (US) and then get sick afterward (UR). Later, you feel nauseous (CR) whenever you see or smell that same food (CS), even if the illness wasn’t directly caused by the food.

6. Conditioned Emotional Responses:

• Scenario: A person who had a car accident (US) might experience intense fear (UR). Later, hearing the sound of screeching brakes (CS) causes them to feel afraid (CR) even though they aren’t in danger.

7. Pavlovian Example with Pets:

• Scenario: If you consistently ring a bell (CS) before feeding your cat, eventually your cat will start to come running (CR) at the sound of the bell, even before the food is presented.

Why is Respondent Conditioning useful in ABA Therapy?

Creating Positive Associations for New Environments or Experiences

• For children who may have difficulty in new environments (e.g., school, therapy sessions), pairing those environments with positive experiences can help reduce resistance and anxiety.

• Example: By associating the therapy room with fun activities or rewards, a child begins to feel safe and comfortable in that space, making them more receptive to learning and intervention.

Managing Sensory Sensitivities

• Many children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) experience sensory sensitivities, such as aversion to certain sounds, textures, or lights. Respondent conditioning can help reduce these sensitivities by pairing the aversive stimulus with something positive.

• Example: If a child is sensitive to the sound of a vacuum, the therapist can gradually introduce the sound while pairing it with something enjoyable (like a favorite toy or game). Over time, this can help the child develop tolerance or reduce their reaction to the sound.

Increasing Comfort with Social Situations

• Respondent conditioning helps build comfort in social situations that may initially be overwhelming. By associating social activities with positive reinforcement, children can become more comfortable interacting with others.

• Example: If a child is anxious around peers, they might start by observing play from a safe distance while engaging in a rewarding activity. Gradually, they’re encouraged to get closer, helping them associate peer interactions with safety and enjoyment.

Encouraging Healthy Habits and Daily Routines

By pairing less preferred activities (like brushing teeth or washing hands) with positive reinforcement, children can develop a more positive response to daily routines.

• Example: If a child dislikes brushing their teeth, the therapist might pair brushing with a preferred activity or reward immediately afterward. Over time, brushing becomes a positive experience.

Respondent conditioning in ABA therapy allows practitioners to shape behaviors, making new experiences less intimidating and increasing positive associations with daily routines. This creates a foundation for learning and supports the overall goals of ABA therapy, making it easier for individuals to acquire new skills and adjust to various environments.

Operant Conditioning

In Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), operant conditioning is a method used to shape voluntary behaviors by modifying the consequences that follow those behaviors. It focuses on how behavior is influenced by the outcomes it produces, whether through reinforcement (which increases behavior) or punishment (which decreases behavior).

Key Concepts in Operant Conditioning:

1. Reinforcement – Increases the likelihood of a behavior:

• Positive Reinforcement: Adding something desirable (e.g., praise, rewards) to increase a behavior.

• Negative Reinforcement: Removing something aversive (e.g., stopping a loud noise) to increase a behavior.

2. Punishment – Decreases the likelihood of a behavior:

• Positive Punishment: Adding something aversive (e.g., extra chores) to decrease a behavior.

• Negative Punishment: Removing something desirable (e.g., taking away privileges) to decrease a behavior.

3. Discriminative Stimulus (SD): A cue or signal that a particular behavior will be reinforced or punished.

4. Shaping: Gradually reinforcing successive approximations of a desired behavior, helping individuals learn complex behaviors step by step.

Real World Scenarios for Operant Conditioning

1. Positive Reinforcement (Adding something desirable to increase behavior):

• Scenario: A manager praises an employee for completing a project ahead of schedule. The praise (positive reinforcement) increases the likelihood that the employee will work hard to complete future projects early.

2. Negative Reinforcement (Removing something aversive to increase behavior):

• Scenario: A car beeps until you fasten your seatbelt. The beeping stops (negative reinforcement) when the seatbelt is fastened, which encourages you to buckle up as soon as you enter the car.

3. Positive Punishment (Adding something aversive to decrease behavior):

• Scenario: A child touches a hot stove and feels pain. The pain (positive punishment) decreases the likelihood that the child will touch the stove again.

4. Negative Punishment (Removing something desirable to decrease behavior):

• Scenario: A teenager loses their phone privileges for a week after breaking curfew. The removal of phone privileges (negative punishment) makes it less likely that they’ll break curfew again.

Note: always consider the ethical dilemma of implementing Negative Reinforcement and Positive and Negative Punishment

Additional Real-World Examples of Operant Conditioning Components.

1. Using Reinforcement in Education:

• Scenario: A teacher gives extra playtime to students who finish their assignments on time. The extra playtime (positive reinforcement) increases students’ motivation to complete their work.

2. Avoidance Through Negative Reinforcement:

• Scenario: A person takes an umbrella to avoid getting wet in the rain. The avoidance of getting wet (negative reinforcement) increases the likelihood of taking an umbrella in future rainy weather.

3. Positive Punishment in Sports:

• Scenario: A coach assigns extra laps when a player arrives late to practice. The additional laps (positive punishment) discourage the player from being late again.

4. Time-Out as Negative Punishment:

• Scenario: A child is placed in time-out after they hit another child. The removal of playtime (negative punishment) aims to reduce aggressive behavior.

5. Use of Discriminative Stimulus (SD):

• Scenario: A “Sale” sign in a store encourages shoppers to look at items. The sign (SD) signals that buying items will result in savings, making shoppers more likely to buy during a sale.

6. Behavioral Shaping Using Reinforcement:

• Scenario: In dog training, a trainer rewards the dog each time it gets closer to performing a desired trick (e.g., rolling over). Gradually, the dog learns to perform the full trick through incremental positive reinforcement.

Here are additional examples of shaping in operant conditioning, where complex behaviors are taught step-by-step by reinforcing successive approximations toward the desired behavior:

1. Teaching a Child to Tie Their Shoes

• Step 1: Reward the child for picking up the laces.

• Step 2: Once they consistently pick up the laces, reward them for crossing them over each other.

• Step 3: Next, reward them for making the initial loop.

• Step 4: Continue reinforcing each step until the child can tie the shoes independently.

• Goal: The child learns to tie their shoes by receiving reinforcement at each stage of the process.

2. Improving Handwriting in a Student

• Step 1: Praise the student for correctly holding the pencil.

• Step 2: Once the grip is consistent, reinforce any attempt to form letters, even if not perfect.

• Step 3: Gradually reinforce the child only when letters are closer to the correct shape.

• Step 4: Eventually, praise the child for forming letters neatly and correctly.

• Goal: The student’s handwriting improves over time through reinforcement at each incremental improvement.

3. Teaching a Dog to Fetch

• Step 1: Give the dog a treat for looking at the ball.

• Step 2: Once the dog consistently looks at the ball, reward it for moving toward the ball.

• Step 3: Next, reward the dog only when it touches or nudges the ball.

• Step 4: Finally, reward the dog for picking up the ball and bringing it back.

• Goal: The dog learns to fetch by receiving rewards at each step of the behavior chain.

4. Learning to Ride a Bicycle

• Step 1: Reinforce the child for sitting on the bike.

• Step 2: Once they are comfortable, reward them for keeping their balance with training wheels.

• Step 3: After that, reward them for pedaling while the training wheels provide less support.

• Step 4: Finally, reward them for pedaling and balancing independently without training wheels.

• Goal: The child learns to ride the bike without training wheels, with reinforcement provided at each new milestone.

5. Developing Speech in a Child with Limited Verbal Skills

• Step 1: Reinforce the child for making any vocal sounds.

• Step 2: Once sounds are consistent, reinforce only when the child makes sounds that resemble words.

• Step 3: Gradually reinforce for specific words or sounds that resemble desired words (e.g., “ma” for “mama”).

• Step 4: Finally, reinforce the child for saying whole words and later short sentences.

• Goal: The child progresses from sounds to words, with reinforcement guiding each step in speech development.

6. Improving Focus During Homework Time

• Step 1: Praise and reward the child for sitting at the desk for a few minutes.

• Step 2: Once the child sits for a few minutes regularly, reinforce them for picking up a pencil and beginning the assignment.

• Step 3: Gradually increase the amount of time they are expected to focus on homework before receiving reinforcement.

• Step 4: Eventually, reinforce for completing the entire homework session with focus.

• Goal: The child learns to focus for extended periods, with reinforcement provided at incremental increases in focus duration.

7. Building Independence in Toothbrushing

• Step 1: Reward the child for picking up the toothbrush.

• Step 2: Once this is consistent, reward them for putting toothpaste on the brush.

• Step 3: Next, reinforce brushing for a few seconds.

• Step 4: Gradually increase the time of brushing until the child can complete the full routine independently.

• Goal: The child learns to brush their teeth independently through reinforcement at each successive step.