B.8. Identify and distinguish among unconditioned, conditioned, and generalized punishers.

Unconditioned Punishers

• Definition: Unconditioned punishers (also called primary punishers) are stimuli that naturally decrease the likelihood of a behavior without prior learning or conditioning. They are typically related to biological or physical discomfort.

• Characteristics:

• Innate; no prior experience or learning is needed for these to be effective.

• Often relate to pain or discomfort.

• Examples:

• Physical Pain: Touching a hot stove causes pain, which decreases the likelihood of touching it again.

• Extreme Cold or Heat: Exposure to freezing temperatures discourages a person from going outside unprotected in cold weather.

• Loud, Startling Noises: Sudden, loud sounds can be aversive and decrease the behavior that produced the sound (e.g., slamming a door).

Conditioned Punishers

• Definition: Conditioned punishers (also known as secondary punishers) are stimuli that decrease the likelihood of a behavior through learned association with unconditioned or other conditioned punishers. They do not inherently cause discomfort but acquire their punishing qualities through experience.

• Characteristics:

• Acquired through pairing with primary punishers or other aversive experiences.

• Effectiveness is learned rather than natural.

• Examples:

• Social Disapproval: A person receives a frown or negative remark after interrupting someone. Through experience, they learn to avoid interrupting to escape social disapproval.

• Loss of Privileges: A child loses TV time after breaking a rule. Although TV time itself isn’t inherently unpleasant, losing it is punishing due to the association with the loss of enjoyment.

• Traffic Tickets: A person receives a speeding ticket, which, over time, conditions them to avoid speeding to avoid future fines.

Generalized Punishers

• Definition: Generalized punishers are a type of conditioned punisher that has been paired with a variety of other punishers, making it effective in many situations and with most individuals. Because it is associated with multiple types of punishment, a generalized punisher is broadly effective.

• Characteristics:

• Punishes behavior across many different situations.

• Less dependent on specific conditions or experiences.

• Examples:

• Social Rejection or Criticism: Negative social feedback, such as criticism, is a generalized punisher because it can signify multiple types of aversive outcomes (e.g., loss of friendship, loss of respect).

• Disapproval from Authority Figures: A student or employee may alter behavior to avoid disapproval from teachers, bosses, or parents. The generalized fear of disappointing authority figures often serves as a broad punisher.

• Time-Out in a Variety of Settings: Time-out from reinforcement (e.g., in classrooms, homes) becomes a generalized punisher when it has been consistently associated with various forms of loss (e.g., loss of playtime, social interaction, attention).

Summary of Key Differences

• Unconditioned Punishers: Naturally punishing stimuli that require no learning to reduce behavior (e.g., pain, extreme temperatures).

• Conditioned Punishers: Acquire punishing qualities through association with other aversive stimuli or consequences (e.g., social disapproval, fines).

• Generalized Punishers: Conditioned punishers that are effective across many settings due to associations with various punishers (e.g., social rejection, authority disapproval).

Here are real-world scenarios that illustrate unconditioned, conditioned, and generalized punishes:

Unconditioned Punisher Scenarios

1. Burning Hand on a Hot Stove: A child touches a hot stove and immediately feels pain, making it highly unlikely they will touch it again. The pain serves as an unconditioned punisher.

2. Walking Outside in Extreme Cold: A person steps outside without a coat on a freezing day. The cold is so uncomfortable that they quickly go back inside, reducing the likelihood they’ll go outside unprepared again.

3. Hearing a Sudden Loud Noise: A person is startled by a loud siren when standing too close to an emergency vehicle. The startling noise is uncomfortable, discouraging them from standing near loud vehicles in the future.

Conditioned Punisher Scenarios

1. Traffic Ticket for Speeding: A driver receives a speeding ticket. Although the ticket itself is just paper, it’s associated with financial loss and the inconvenience of paying a fine. Over time, the sight of police cars may act as a conditioned punisher, prompting the driver to slow down.

2. Reprimand from a Teacher: A student talks during a lecture and receives a disapproving look from the teacher, who then tells them to be quiet. The reprimand discourages the student from talking out of turn in the future, as they associate the teacher’s reaction with an unpleasant experience.

3. Phone Confiscation for Misbehavior: A teenager misbehaves, and their parents confiscate their phone as a consequence. Losing access to their phone is punishing and reduces the likelihood of misbehavior, as they associate their actions with the loss of a valued item.

Generalized Punisher Scenarios

1. Social Disapproval on Social Media: A teenager posts a controversial opinion on social media and receives critical comments and a few “unfollows.” The social disapproval and loss of followers act as a generalized punisher, reducing the likelihood they will post similar content in the future due to the broad impact of social rejection.

2. Time-Out for Multiple Misbehaviors: A child is placed in time-out whenever they misbehave, whether it’s interrupting, refusing to follow instructions, or taking a toy from a peer. Because time-out consistently removes them from enjoyable activities across multiple situations, it acts as a generalized punisher that reduces a range of undesirable behaviors.

3. Disapproval from a Boss: An employee misses a deadline and receives an email expressing disappointment from their boss. This disapproval not only signals a potential risk to their job but also feels socially rejecting. This generalized punishment discourages the employee from missing deadlines again, as they associate the boss’s disapproval with multiple negative outcomes.

Key Takeaway

These scenarios demonstrate how unconditioned punishers naturally decrease behavior due to their inherent unpleasantness, conditioned punishers acquire punishing qualities through association with other negative outcomes, and generalized punishers are broadly effective because they are linked to multiple aversive consequences across situations. Recognizing these differences is valuable in applied behavior analysis to select appropriate interventions for reducing specific behaviors.

B.9. Identify and Distinguish Among Simple Schedules of Reinforcement

Understanding reinforcement schedules is essential for behavior analysts, as these schedules determine how often a behavior will be reinforced, influencing its strength and consistency. Here’s a breakdown of simple reinforcement schedules to help clarify each type:

1. Continuous Reinforcement (CRF)

• Definition: Every occurrence of the target behavior is reinforced.

• Example: A child receives praise each time they complete a math problem.

• When to Use: Ideal for teaching new skills or strengthening behaviors in the early stages.

2. Intermittent Reinforcement (INT)

• Definition: Only some occurrences of the target behavior are reinforced, which makes the behavior more resistant to extinction.

• Types of Intermittent Reinforcement:

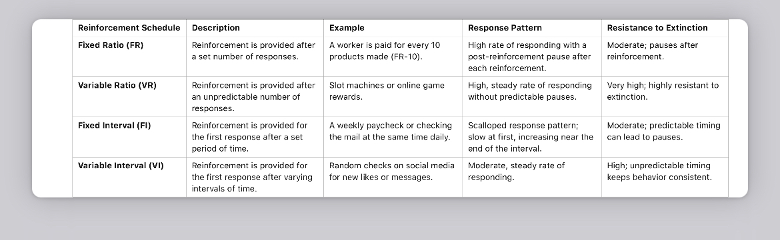

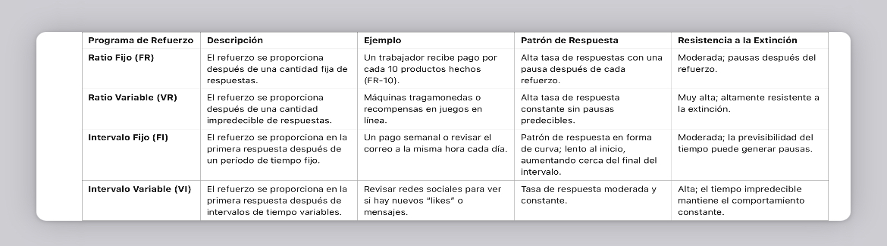

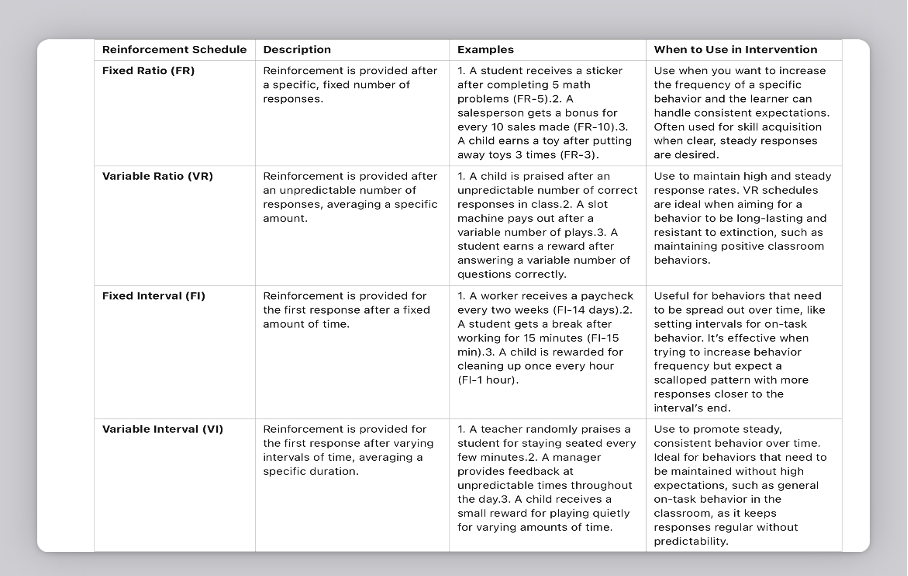

• Fixed Ratio (FR): Reinforcement is provided after a fixed number of responses.

• Example: A worker is paid after producing every 10 units.

• Variable Ratio (VR): Reinforcement is provided after a variable number of responses, based on an average.

• Example: Slot machines, which pay out after an unpredictable number of plays.

• Fixed Interval (FI): Reinforcement is provided for the first response after a fixed period.

• Example: A student receives a break every 30 minutes if they remain on-task.

• Variable Interval (VI): Reinforcement is provided for the first response after varying time intervals, based on an average.

• Example: Checking for a message on your phone when notifications arrive at random times.

Key Distinctions:

• Ratio Schedules focus on the number of responses (FR and VR), while Interval Schedules focus on the passage of time (FI and VI).

• Fixed Schedules have a predictable pattern, whereas Variable Schedules provide reinforcement in an unpredictable manner, generally leading to more consistent response rates. “Variable Ratio (VR) schedules” refer to a type of reinforcement schedule in which a response is rewarded after an unpredictable number of actions or responses. Because the reinforcement is given at variable times, the subject does not know when the next reward will come, which leads to a high, steady rate of responding. The term “particularly resistant to extinction” means that behaviors reinforced on a Variable Ratio schedule are less likely to stop or decrease even when the reinforcement (reward) is no longer provided. In other words, the behavior persists for a long time without rewards because the subject has learned that rewards may come unpredictably, making them more motivated to keep trying. This is why VR schedules are used in contexts where long-lasting, persistent behavior is desired—such as gambling or certain types of training.

A common example of a Variable Ratio (VR) schedule is a slot machine in a casino. Slot machines operate on a VR schedule because players do not know when they will win. Sometimes they might win after just a few spins, while other times, it could take hundreds of spins. Since the reinforcement (the payout) occurs unpredictably, players are motivated to keep playing, as each spin could potentially be the winning one. This uncertainty creates persistence in the behavior, making it highly resistant to extinction; players continue to play even without frequent wins because they are conditioned to expect a reward might come with any spin.

In Practice:

Each schedule has unique effects on behavior. For instance, Variable Ratio (VR) schedules are particularly resistant to extinction, making them useful for maintaining long-term behavior, while Fixed Ratio (FR) schedules can lead to a high response rate but may cause a “pause” after reinforcement is delivered (post-reinforcement pause).

A post-reinforcement pause in a Fixed Ratio (FR) schedule is a brief pause or break in responding that typically occurs right after a behavior is reinforced. In an FR schedule, reinforcement is delivered after a set number of responses (e.g., every 10 responses). Once the subject receives the reinforcement, they often take a short pause before starting the behavior again.

For example, if a worker is paid after assembling 10 products (an FR-10 schedule), they might pause for a moment after reaching the 10th product before starting on the next set. This pause happens because the reinforcement was just received, and there’s a set amount of effort required before the next reinforcement is given.

A Fixed Ratio (FR) schedule with post-reinforcement pause could look like this: Imagine a content creator who gains a new follower after every 5 posts they publish. After they receive the “reinforcement” of a new follower, they might feel motivated by that gain, but they know it will take another 5 posts to see the next follower. So, after receiving a follower, they might take a short break before starting to create more content, as they anticipate that additional effort will be required before gaining the next follower. This brief pause is the post-reinforcement pause.

In social media terms, this break could be seen as a rest period after receiving engagement or validation, with the creator returning to post more consistently once they’re ready to work toward the next “goal” or reinforcement milestone.

Understanding and distinguishing these schedules is critical for designing effective reinforcement plans in behavior intervention.

Summary Table B.9 Identify and distinguish among a simple schedule or reinforcement

1. Skill Acquisition in a Classroom

In a classroom, if a BCBA is teaching a student a new skill, like solving math problems, they might use a Fixed Ratio (FR) schedule. For instance, the student could receive a small reward after completing every three math problems (FR-3). This encourages consistent performance and sets clear goals while the student is learning a new skill.

2. Increasing Participation in Group Therapy

To encourage consistent participation in a group therapy setting, a BCBA might use a Variable Ratio (VR) schedule. For example, a student could receive praise or a token for contributing to the discussion an unpredictable number of times, such as after 2, 5, or 7 contributions. This helps maintain steady engagement in group discussions without predictability.

3. Encouraging Timely Arrival in a Workplace

For employees who struggle with punctuality, a BCBA might implement a Fixed Interval (FI) schedule, rewarding the employee if they arrive on time consistently over a set period, like every two weeks. This reinforces the behavior of punctuality and helps the employee maintain a regular routine.

4. Promoting Focus During Long Tasks

When a student needs to stay focused for extended periods, such as during independent work, a BCBA could use a Variable Interval (VI) schedule. The student might receive praise or a small reward at random intervals while staying on task, such as after 10, 15, or 20 minutes. This approach encourages steady focus without making the timing predictable.

5. Reducing Disruptive Behaviors in Therapy

In an individual therapy session, if a BCBA is aiming to reduce a behavior (like calling out), they might use a Fixed Ratio (FR) schedule. For instance, the child could be reinforced after every third instance of waiting appropriately or raising their hand (FR-3). This approach provides clear feedback and encourages gradual improvement in managing the disruptive behavior.

6. Maintaining Generalized Positive Behavior

To ensure that a positive behavior, such as polite greetings, continues across various settings, a BCBA might use a Variable Ratio (VR) schedule. For example, the client might receive a compliment or small reward randomly after different numbers of polite greetings, like after 2, 4, or 6 greetings. This schedule makes the behavior more resistant to extinction because the client can’t predict when reinforcement will occur.

7. Sustaining Attention for a Group Task

In a group activity where all participants need to stay engaged, such as a cooperative game or project, a Fixed Interval (FI) schedule could be effective. For instance, the group might receive positive reinforcement, like verbal praise or points, every 10 minutes of working cooperatively. This schedule helps sustain attention and cooperation over the activity’s duration.

8. On-Task Behavior in Non-Structured Settings

In less structured environments, like a library where a student is expected to stay quiet and read, a BCBA could use a Variable Interval (VI) schedule. The student might receive praise or a small reward at random times for quietly reading. This approach encourages consistent on-task behavior without predictability, which works well in non-structured settings. These examples show how each reinforcement schedule can be applied in various real-world scenarios to meet specific behavioral goals.

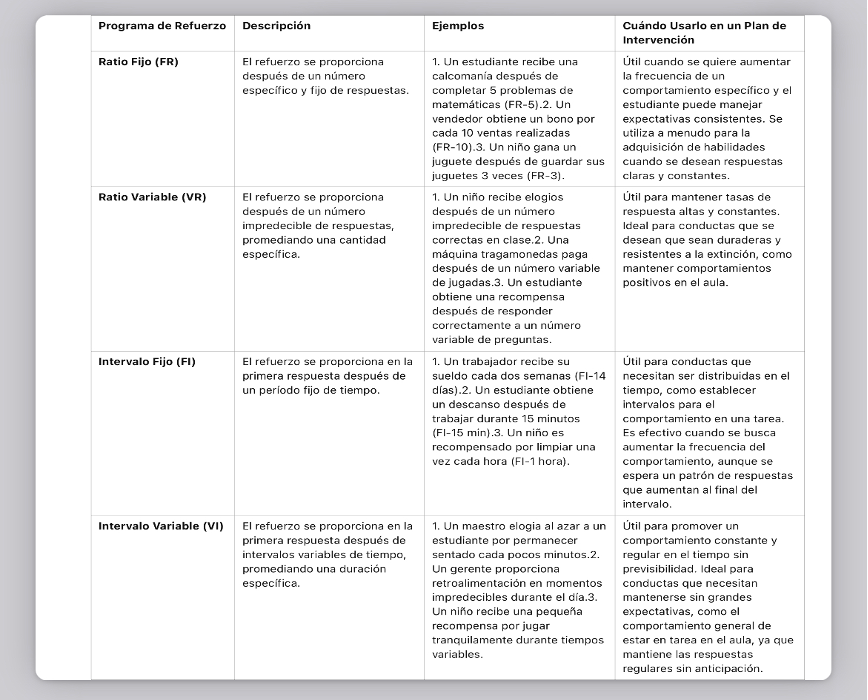

Aquí ofrecemos ejemplos en español para que nuestros estudiantes de habla hispana aprendan como elegir un programa de refuerzo específico en su futura practica como BCBAs:

1. Adquisición de Habilidades en el Aula

En un aula, si un BCBA está enseñando una nueva habilidad a un estudiante, como resolver problemas de matemáticas, podría utilizar un programa de Ratio Fijo (FR). Por ejemplo, el estudiante podría recibir una pequeña recompensa después de completar cada tres problemas de matemáticas (FR-3). Esto fomenta un rendimiento consistente y establece metas claras mientras el estudiante aprende la nueva habilidad.

2. Aumento de la Participación en Terapia Grupal

Para fomentar la participación constante en una terapia grupal, un BCBA podría utilizar un programa de Ratio Variable (VR). Por ejemplo, el estudiante podría recibir elogios o un token por contribuir a la discusión después de un número impredecible de veces, como después de 2, 5 o 7 contribuciones. Esto ayuda a mantener un compromiso constante en las discusiones grupales sin previsibilidad.

3. Fomentar la Puntualidad en un Lugar de Trabajo

Para empleados que tienen dificultades con la puntualidad, un BCBA podría implementar un programa de Intervalo Fijo (FI), recompensando al empleado si llega a tiempo de forma consistente durante un período establecido, como cada dos semanas. Esto refuerza el comportamiento de puntualidad y ayuda al empleado a mantener una rutina regular.

4. Fomentar la Concentración en Tareas Largas

Cuando un estudiante necesita permanecer concentrado por períodos largos, como en trabajo independiente, un BCBA podría usar un programa de Intervalo Variable (VI). El estudiante podría recibir elogios o una pequeña recompensa en intervalos aleatorios mientras permanece en la tarea, como después de 10, 15 o 20 minutos. Este enfoque fomenta una concentración constante sin que el tiempo de recompensa sea predecible.

5. Reducir Comportamientos Disruptivos en Terapia

En una sesión de terapia individual, si un BCBA tiene como objetivo reducir un comportamiento (como interrumpir o hablar fuera de turno), podría usar un programa de Ratio Fijo (FR). Por ejemplo, el niño podría recibir refuerzo después de cada tercera vez que espere apropiadamente o levante la mano (FR-3). Este enfoque proporciona retroalimentación clara y fomenta una mejora gradual en el manejo del comportamiento disruptivo.

6. Mantener Comportamientos Positivos Generalizados

Para asegurar que un comportamiento positivo, como los saludos corteses, continúe en varios entornos, un BCBA podría usar un programa de Ratio Variable (VR). Por ejemplo, el cliente podría recibir un elogio o una pequeña recompensa de forma aleatoria después de diferentes números de saludos corteses, como después de 2, 4 o 6 saludos. Este programa hace que el comportamiento sea más resistente a la extinción, ya que el cliente no puede predecir cuándo ocurrirá el refuerzo.

7. Mantener la Atención en una Tarea Grupal

En una actividad grupal donde todos los participantes necesitan mantenerse comprometidos, como un juego cooperativo o un proyecto, un programa de Intervalo Fijo (FI) podría ser efectivo. Por ejemplo, el grupo podría recibir refuerzo positivo, como elogios verbales o puntos, cada 10 minutos de trabajo cooperativo. Este programa ayuda a mantener la atención y cooperación durante la actividad.

Claro, aquí tienes el punto 8 completo:

8. Mantener el Comportamiento en Tareas en Entornos No Estructurados

En entornos menos estructurados, como una biblioteca donde se espera que un estudiante permanezca en silencio y lea, un BCBA podría usar un programa de Intervalo Variable (VI). El estudiante podría recibir elogios o una pequeña recompensa en momentos aleatorios por leer en silencio. Este enfoque fomenta un comportamiento constante y en tarea sin previsibilidad, lo cual funciona bien en entornos no estructurados, ya que mantiene al estudiante comprometido sin anticipar cuándo recibirá el refuerzo.