B.10. Identify and distinguish among concurrent, multiple, mixed, and chained schedules of reinforcement.

1. Concurrent Schedules of Reinforcement

• Definition: Concurrent schedules involve two or more reinforcement schedules that are available simultaneously and independently, allowing an individual to choose between them. This is often used to understand choice-making behavior, as it gives the learner options for different responses, each linked to its own reinforcement schedule.

• Example: In a classroom, a student could choose between doing math problems (earning praise after every 5 correct answers, a Fixed Ratio schedule) or reading a book (earning a sticker every 10 minutes of reading quietly, a Fixed Interval schedule). The student can switch between tasks, showing how they allocate time based on which activity they find more reinforcing.

2. Multiple Schedules of Reinforcement

• Definition: Multiple schedules involve two or more distinct reinforcement schedules presented alternately, but only one schedule is in effect at any given time. Each schedule is signaled by a different stimulus, so the individual knows which schedule is active. This is often used to teach flexibility or context-specific behaviors.

• Example: A child receives reinforcement for reading at home under a Fixed Interval schedule (e.g., every 15 minutes of reading). At school, they receive reinforcement for reading under a Variable Ratio schedule (e.g., receiving praise after an unpredictable number of pages). Each setting provides a different signal (e.g., location) that indicates which reinforcement schedule is active.

3. Mixed Schedules of Reinforcement

• Definition: Mixed schedules are similar to multiple schedules in that two or more schedules alternate, but there is no distinct signal to indicate which schedule is currently active. The individual must respond to each schedule as it occurs, learning to adapt even though the schedule type is not explicitly indicated.

• Example: In a social skills session, a child might receive reinforcement for initiating a conversation. Sometimes the reinforcement follows a Fixed Ratio (FR-3) schedule (after three initiations), and sometimes it follows a Variable Interval (VI-10) schedule (after approximately every 10 minutes). Since there’s no signal for when each schedule changes, the child learns to initiate conversations without knowing precisely when reinforcement will come.

4. Chained Schedules of Reinforcement

• Definition: Chained schedules involve two or more reinforcement schedules that must occur in a specific order, with each step acting as a condition for the next. The reinforcement is only given after completing the entire sequence. Each part of the chain is often associated with a different stimulus, guiding the learner through the steps.

• Example: A BCBA might design a chained schedule for handwashing. The learner is reinforced only after completing each step in the correct sequence: turning on the faucet, wetting hands, applying soap, scrubbing, rinsing, and drying hands. Completing each step cues the next one, and only after finishing all steps does the learner receive reinforcement (e.g., praise or a token).

Summary of When to Use Each Schedule

• Concurrent Schedule: Use when promoting choice-making or examining preferences, as it allows individuals to choose between behaviors based on available reinforcers.

• Multiple Schedule: Use when the goal is to teach context-specific behavior. The different signals help the individual learn to adjust behavior based on the setting or context.

• Mixed Schedule: Use when aiming to generalize behavior in varied situations without relying on signals. Mixed schedules help learners respond consistently even when conditions are unpredictable.

• Chained Schedule: Use when teaching a complex sequence of behaviors that must be completed in a specific order. Chained schedules are effective for multi-step tasks like daily routines or job skills.

Each schedule of reinforcement serves unique purposes and is chosen based on the goals of the intervention, the learning context, and the individual’s needs.

Summary Table B10

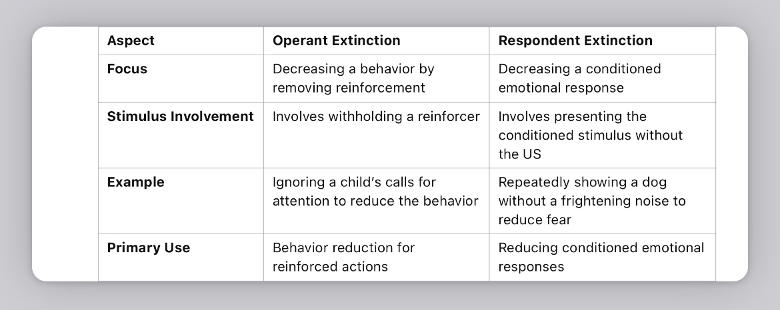

B.11. Identify and distinguish between operant and respondent extinction as operations and processes.

Operant Extinction

• Definition: Operant extinction occurs when a behavior that was previously reinforced is no longer followed by reinforcement, leading to a decrease in that behavior over time.

• Process: In operant extinction, a behavior is weakened by stopping the reinforcement that previously followed it. Initially, the behavior might temporarily increase in frequency, intensity, or duration (known as an extinction burst) before it starts to decrease.

• Example: If a student previously received attention (reinforcer) each time they called out in class, stopping the attention (ignoring the call-outs) would likely lead to a decrease in the calling-out behavior over time.

• When to Use: Operant extinction is used when reducing or eliminating a behavior that was previously maintained by reinforcement. It’s important to identify the specific reinforcer maintaining the behavior to effectively apply extinction.

Respondent Extinction

• Definition: Respondent extinction refers to the process of weakening a conditioned response by repeatedly presenting the conditioned stimulus (CS) without the unconditioned stimulus (US).

• Process: In respondent extinction, the conditioned response gradually decreases when the conditioned stimulus is presented without the unconditioned stimulus that originally caused the response.

• Example: A child has a conditioned fear of dogs because they were once frightened by a loud noise (US) when they saw a dog (CS). Through respondent extinction, if the child repeatedly encounters dogs without the frightening noise, their fear of dogs would gradually decrease.

• When to Use: Respondent extinction is used to reduce a learned or conditioned emotional response, such as fear or anxiety. It’s common in therapeutic settings where the goal is to decrease negative emotional reactions by separating the conditioned stimulus from the unconditioned stimulus.

Summary

• Operant Extinction: Reduces behaviors that were previously reinforced by stopping the reinforcement. Commonly used for behaviors maintained by attention, escape, or other reinforcers.

• Respondent Extinction: Weakens conditioned emotional responses by presenting the conditioned stimulus without the unconditioned stimulus. Often used in therapy for phobias or anxiety.

By understanding these differences, practitioners can choose the appropriate extinction strategy depending on whether they are targeting learned behaviors or conditioned emotional responses.

Here are real-world scenarios where a BCBA might need to identify whether to implement operant extinction or respondent extinction based on the nature of the behavior:

Scenario 1: Attention-Seeking Behavior in a Classroom

• Behavior: A child in a classroom frequently interrupts by calling out for the teacher’s attention.

• Analysis: The behavior is likely maintained by the attention the child receives from the teacher and classmates when they call out.

• Intervention – Operant Extinction: The BCBA could recommend operant extinction by advising the teacher to stop giving attention to the child when they call out (e.g., ignoring or not responding to interruptions). Over time, without reinforcement, the calling-out behavior should decrease.

Scenario 2: Fear of Dogs Due to a Past Frightening Experience

• Behavior: A child becomes anxious and fearful whenever they see a dog, due to a previous experience where a loud noise startled them in the presence of a dog.

• Analysis: This is a conditioned emotional response; the sight of a dog (conditioned stimulus) has become associated with fear (conditioned response) due to the past frightening event (unconditioned stimulus).

• Intervention – Respondent Extinction: The BCBA could recommend respondent extinction by gradually exposing the child to calm, friendly dogs in a controlled environment without any frightening stimuli. Repeated exposure should weaken the conditioned fear response, as the child learns that seeing a dog does not predict a frightening experience.

Scenario 3: Child Whining to Get Candy in a Store

• Behavior: A child whines or cries to get candy whenever they visit the store with their parent.

• Analysis: The whining is likely maintained by the parent giving in and buying candy (reinforcer) to stop the whining.

• Intervention – Operant Extinction: The BCBA could suggest operant extinction by advising the parent to consistently stop giving candy in response to whining. The initial whining may increase (extinction burst), but with time and consistency, the whining should decrease as it is no longer reinforced by candy.

Scenario 4: Fear of Balloons Due to a Startling Pop

• Behavior: A child has developed a fear of balloons due to a previous experience where a balloon popped loudly, startling them.

• Analysis: The sight of a balloon has become a conditioned stimulus that triggers anxiety (conditioned response) because of the loud pop (unconditioned stimulus).

• Intervention – Respondent Extinction: The BCBA could use respondent extinction by gradually exposing the child to balloons in a calm environment, without any popping. Over time, the child’s fear of balloons should decrease, as they learn that the presence of a balloon does not predict a frightening sound.

Scenario 5: Child Engaging in Escape-Maintained Behavior

• Behavior: A child tries to leave their seat during class when given a challenging task, and the teacher often lets them take breaks.

• Analysis: The behavior of leaving the seat is likely maintained by escaping or avoiding difficult tasks (negative reinforcement).

• Intervention – Operant Extinction: The BCBA could suggest operant extinction by advising the teacher to no longer allow escape from tasks when the child leaves their seat. Instead, the teacher could redirect the child back to their seat to complete the task, which should decrease the behavior over time as it is no longer effective in avoiding the task.

Scenario 6: Child Exhibiting Anxiety Around Specific Toys Due to a Scary Event

• Behavior: A child becomes anxious when they see a particular type of toy after being frightened by it once.

• Analysis: The toy has become a conditioned stimulus that elicits a fear response due to its association with a frightening event.

• Intervention – Respondent Extinction: The BCBA could recommend gradually reintroducing the toy in a safe, positive context without any frightening stimuli. Over time, through respondent extinction, the child’s anxiety around the toy should decrease.

Summary:

• Operant Extinction is chosen for behaviors maintained by reinforcement, like attention-seeking, escape, or tangible rewards.

• Respondent Extinction is chosen to reduce conditioned emotional responses, such as fear or anxiety due to past associations.

In these scenarios, the BCBA’s task is to determine the function of the behavior (operant or respondent) and then implement the appropriate extinction strategy to address it effectively.

B.12. Identify examples of stimulus control.

Stimulus control refers to situations where a specific stimulus (such as a cue or signal) consistently triggers a particular behavior because the behavior has been reinforced in the presence of that stimulus. Here are some examples:

1. Traffic Lights: When a traffic light turns green, drivers go, and when it’s red, they stop. The light acts as a stimulus that controls the behavior (driving or stopping).

2. School Bell: In schools, students often pack up and prepare to leave when they hear the dismissal bell. The sound of the bell acts as a stimulus, controlling the behavior of transitioning to the next activity.

3. Phone Notifications: When a phone vibrates or chimes, people often check their phone. The notification sound is a stimulus that prompts the behavior of looking at the screen.

4. Open/Closed Signs in Stores: People are likely to enter a store when the sign reads “Open” and avoid it when it says “Closed.” The sign controls the behavior of entering or avoiding the store.

5. Classroom Hand-raising: In a classroom, students may raise their hands to speak because they know they’ll get called on. The teacher’s rule (only speak when called on) acts as a stimulus, controlling the behavior.

6. Text Message Alerts: Many people feel compelled to read a text message immediately upon hearing an alert sound. The sound acts as a cue (stimulus) to engage in reading behavior.

7. Speed Limit Signs: Drivers tend to adjust their speed based on posted speed limits, especially when they know they’re in an area with active law enforcement. The sign acts as a stimulus that controls the behavior (speed adjustment).

In these examples, the specific stimulus reliably triggers certain behaviors due to past reinforcement or consequences experienced in similar situations.

NOTE: If a person does not respond as expected to a stimulus, it may indicate that the stimulus is not functioning as an effective discriminative stimulus (SD). An SD is a cue or signal that indicates the availability of reinforcement for a specific behavior. For a stimulus to be an effective SD, there must be a history of reinforcement associated with that behavior in the presence of the stimulus.

When a person does not respond as expected, it may mean:

• The stimulus is not strong enough or does not stand out sufficiently from other stimuli.

• The behavior has not been reinforced in the presence of the stimulus often enough or recently enough.

• Competing stimuli are present that draw attention away from the SD or lead to other behaviors.

In some cases, the stimulus might be considered a neutral stimulus if it has not been associated with any particular reinforcement history, meaning it has no specific control over behavior.

Here’s a real-world scenario where a BCBA might implement stimulus control to help a client develop appropriate social behaviors in the classroom.

Scenario: Teaching a Child with Autism to Raise Their Hand Before Speaking in Class

Background: A child with autism often calls out answers or comments without raising their hand in the classroom, which disrupts the teacher and other students. The BCBA works with the teacher and the child to teach them to raise their hand and wait to be called on before speaking, establishing appropriate stimulus control over the speaking behavior.

Goal: The goal is for the child to speak only when the teacher calls on them after they raise their hand (SD), instead of calling out (S-delta) at other times when the teacher hasn’t given permission.

Steps Taken by the BCBA:

1. Define the Target Behavior:

• Desired Behavior: Raising their hand and waiting to be called on before speaking.

• Undesired Behavior: Calling out answers or comments without raising their hand.

2. Identify the Relevant Stimuli:

• SD (Discriminative Stimulus): The teacher calling on the child after they’ve raised their hand.

• S-delta: Times when the child has not raised their hand or has called out without permission.

3. Teach the Expected Behavior in a Controlled Setting:

• The BCBA starts by teaching this skill in a controlled setting, like a small group session or a practice classroom environment, where the child is taught to raise their hand and wait for the teacher’s response.

4. Use Prompting and Reinforcement:

• When the child raises their hand, the BCBA or teacher immediately reinforces the behavior by calling on them to speak and providing positive feedback (e.g., praise or a token reward).

• If the child calls out without raising their hand, the teacher and BCBA refrain from responding, withholding attention (an extinction approach) to reduce the undesired behavior.

5. Practice Consistently in the Classroom:

• The BCBA works with the classroom teacher to consistently reinforce this hand-raising behavior. Over time, the child learns that only raising their hand and waiting for permission will result in the teacher’s attention and the opportunity to speak.

6. Introduce Natural Reinforcement:

• As the child begins to regularly raise their hand, the BCBA reduces tangible rewards, letting natural reinforcers like teacher praise and peer acknowledgment maintain the behavior.

7. Monitor Progress and Adjust as Needed:

• The BCBA observes the child in the classroom to ensure the hand-raising behavior becomes consistently controlled by the presence of the teacher’s permission (SD).

• If the child struggles, the BCBA may reintroduce prompts or increase reinforcement to strengthen stimulus control.

Outcome:

The child learns to associate hand-raising with receiving the opportunity to speak, understanding that the teacher’s permission is the SD that allows them to talk in class. This stimulus control technique helps the child engage in appropriate classroom behavior, fostering better social interactions and reducing disruptions.

This scenario demonstrates how BCBAs can implement stimulus control to teach socially appropriate behaviors, helping the child respond appropriately to specific environmental cues (like the teacher’s permission) and ignore others (like the urge to call out).

B.13. Identify examples of stimulus discrimination.

Stimulus discrimination occurs when a person or organism learns to respond to one specific stimulus but not to other similar stimuli. This process allows for precise control of behavior in response to different stimuli. Here are some examples:

1. Discriminating Between Letters: A child learns to respond to the letter “B” by calling it “bee” but does not respond in the same way to similar letters like “P” or “D.” The child has learned to distinguish “B” from other letters.

2. Recognizing a Friend’s Voice: In a crowded room, a person can pick out and respond to the voice of a friend among other voices. They have learned to respond specifically to their friend’s voice and not to others.

3. Classroom Rules for Behavior: A student might learn to speak only when they raise their hand in the classroom because the teacher enforces this rule. The same student might talk freely in other settings where raising hands is not required.

4. Dog Responding to Specific Commands: A dog learns to respond to the command “sit” by sitting down but does not respond similarly to other similar-sounding words like “hit” or “fit.”

5. Identifying Correct Answers on a Test: A student learns to choose the correct answer among multiple-choice options by discriminating between the choices, selecting the one that matches the learned content.

6. Store-Specific Discounts: A shopper knows that a discount applies only in one specific store (e.g., Store A) and not in other nearby stores. They will only attempt to use the discount in Store A, not in other similar stores.

7. Professional Tone at Work vs. Casual Tone with Friends: A person speaks formally to colleagues at work but switches to a casual tone with friends. They’ve learned to discriminate between the two social settings and adapt their behavior accordingly.

In these examples, individuals or animals are responding differently to various stimuli based on their unique histories of reinforcement, leading them to discriminate between situations or cues.

BCBAs (Board Certified Behavior Analysts) can determine when to use stimulus discrimination by assessing the specific goals and context of the individual’s behavior, as well as the settings and conditions under which the behavior needs to occur. Here are key steps and considerations for BCBAs in determining when and how to use stimulus discrimination effectively:

1. Define the Target Behavior and Desired Outcome: Determine the specific behavior that needs to occur under certain conditions. For instance, if the goal is for a student to respond only to the teacher’s instructions, BCBAs would focus on promoting discrimination between the teacher’s voice and other voices in the classroom.

2. Identify the Relevant Stimuli: Recognize and isolate the stimuli that should elicit the target behavior (SD) and those that should not (S-delta, or stimuli that do not indicate reinforcement). For example, in a classroom setting, the BCBA might want a child to follow specific classroom routines only when prompted by the teacher, not by classmates or other noises.

3. Evaluate the Reinforcement History: Consider whether the individual already has a history of reinforcement for responding to certain stimuli over others. If not, the BCBA may need to systematically teach the individual to respond only in the presence of the desired stimulus through controlled reinforcement.

4. Create a Controlled Environment: Start teaching stimulus discrimination in a controlled environment with minimal distractions, where the target stimulus is clearly identifiable, and undesired stimuli are limited. For example, when teaching a child to respond to a verbal command, the BCBA might first practice in a quiet setting.

5. Use Differential Reinforcement: Reinforce the target behavior only in the presence of the desired stimulus (SD) and withhold reinforcement in the presence of other stimuli (S-delta). This selective reinforcement helps the individual learn to discriminate between contexts or conditions.

6. Generalize Discrimination Training Gradually: Once the individual responds consistently to the target stimulus in a controlled environment, the BCBA can gradually introduce other stimuli or distractions to ensure the discrimination skill generalizes to natural settings.

7. Monitor for Errors and Adjust: Continuously observe the individual’s responses to see if they are discriminating correctly. If errors occur (e.g., responding to the wrong stimulus), the BCBA may need to increase support, adjust the reinforcement, or provide additional prompts to clarify the differences.

8. Evaluate the Function of the Behavior: Consider the purpose or function of the behavior in the individual’s life. Stimulus discrimination may be most beneficial when it serves a practical or safety-related function, such as knowing when to cross the street (only with a green light) or recognizing a specific signal for help.

9. Consider Social and Environmental Factors: The BCBA should assess if discriminating between stimuli aligns with socially appropriate or desired behaviors in different contexts. For example, teaching a client to respond only to parental instructions for safety-related tasks can be vital in home and community settings.

10. Ensure Ethical and Individualized Use: Tailor the approach to the individual’s developmental level, cognitive abilities, and specific needs, ensuring that discrimination training is used to enhance independence and quality of life.

BCBAs use stimulus discrimination when it’s essential for the individual to respond appropriately to specific cues while ignoring irrelevant or misleading ones, ultimately fostering more adaptive and context-appropriate behaviors.

Scenario: Teaching Safety Skills to a Child with Autism

Background: A young child with autism frequently runs into the street without noticing traffic. This is a dangerous behavior, so the BCBA is working to teach the child to cross the street safely, responding only to the presence of specific traffic signals.

Goal: The BCBA wants the child to cross the street only when they see the pedestrian “walk” signal (SD) and to remain on the sidewalk when the signal says “don’t walk” or if there’s no signal at all (S-delta).

Steps Taken by the BCBA:

1. Identify the Relevant Stimuli:

• SD (Discriminative Stimulus): The “walk” signal.

• S-delta: The “don’t walk” signal or no signal.

2. Introduce the Stimulus in a Controlled Setting:

• The BCBA starts in a quiet, safe environment, such as a mock street area or a quiet residential neighborhood, to minimize distractions and focus on the signals.

3. Teach the Child to Discriminate:

• Using a visual prompt and a verbal cue (e.g., “look for the walking person signal”), the BCBA guides the child to attend to the “walk” signal.

• The child is reinforced (praise, a small reward, or token) every time they correctly wait for the “walk” signal before crossing.

4. Reinforce Desired Behavior:

• The BCBA reinforces the behavior (waiting for the “walk” signal) consistently each time it occurs, and the child is praised for stopping and waiting when there’s no signal or the “don’t walk” signal is displayed.

5. Practice Generalization in Varied Settings:

• Once the child consistently waits for the “walk” signal in the controlled environment, the BCBA gradually practices at real intersections, starting with low-traffic areas and working up to busier streets.

6. Monitor and Adjust as Needed:

• The BCBA observes the child’s behavior closely to ensure they can discriminate reliably between the “walk” and “don’t walk” signals. If the child struggles, the BCBA may increase prompts or reinforcement temporarily to strengthen the discrimination.

7. Fade Prompts Gradually:

• As the child becomes more confident, the BCBA gradually fades prompts, allowing the child to rely solely on the visual cues of the traffic signal.

Outcome:

Over time, the child learns to cross the street only when the “walk” signal is visible, improving safety and independence. The BCBA’s use of stimulus discrimination training has helped the child understand when it’s appropriate to cross, responding only to specific signals and ignoring others, such as moving cars or people crossing at the wrong time.

This scenario illustrates how BCBAs apply stimulus discrimination to teach life-saving safety skills by ensuring the child responds appropriately to specific cues in their environment.

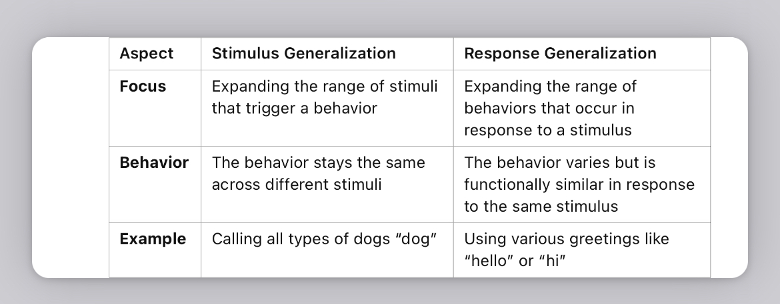

B.14. Identify and distinguish between stimulus and response generalization.

Stimulus generalization and response generalization are two different concepts in behavior analysis that explain how behaviors can transfer or expand beyond the specific conditions in which they were initially learned. Here’s a breakdown of each concept with examples:

Stimulus Generalization

Definition: Stimulus generalization occurs when a learned behavior is performed in the presence of stimuli that are similar to the original stimulus (SD) without further training. In other words, the behavior generalizes across different situations or settings where similar cues or conditions are present.

Example:

• A child learns to say “dog” when they see the family pet. Later, they also say “dog” when they see different types of dogs at a park, even though those dogs look different. Here, the response “dog” generalizes to other similar stimuli (different dogs).

• A student who learns to sit quietly during reading time in one classroom may also sit quietly in other classrooms during reading time.

Purpose: Stimulus generalization helps individuals adapt their learned behaviors to different settings, people, or variations in the environment.

Response Generalization

Definition: Response generalization occurs when a learned stimulus elicits new, untrained responses that are functionally similar to the original response. In this case, the response itself changes or varies, even though the stimulus remains the same.

Example:

• After learning to greet people by saying “hello,” a person may begin to use other greetings like “hi” or “hey” without being specifically taught these new responses. Here, different greetings (responses) are used with the same stimulus (seeing people they know).

• A child is taught to share toys with a peer by handing them over. Later, the child may also start sharing by taking turns or inviting the peer to play, even though they weren’t directly taught these variations.

Purpose: Response generalization helps individuals become more flexible in their behavior, allowing for a variety of appropriate responses to the same stimulus or situation.

In summary:

• Stimulus generalization is when the same behavior occurs in response to different but similar stimuli.

• Response generalization is when different but functionally similar behaviors occur in response to the same stimulus.

Understanding and using both types of generalization effectively helps BCBAs foster adaptability and flexibility in behavior, which is especially beneficial for promoting real-world learning and independence in clients.