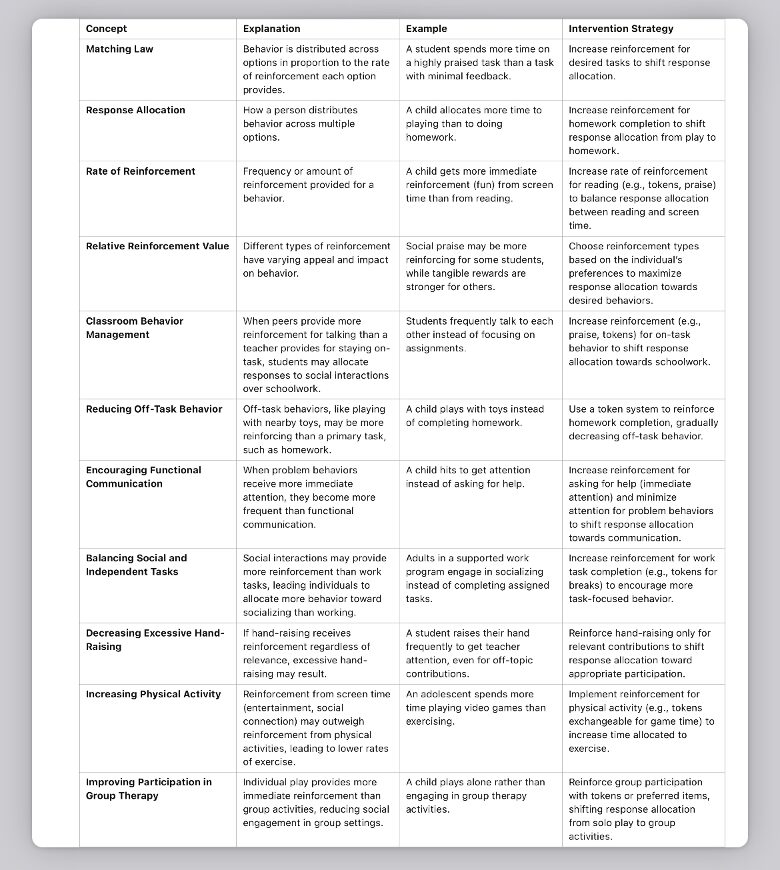

B.23. Identify ways the matching law can be used to interpret response allocation.

The matching law is a principle in behavior analysis that describes how organisms distribute their responses across multiple options when given choices, based on the rates of reinforcement associated with each option.

Understanding the Matching Law

The matching law states that when multiple response options are available, the rate of responding to each option tends to match the rate of reinforcement received from each option. In other words, individuals are likely to allocate their behavior in proportion to the amount and frequency of reinforcement they receive from each option. This principle helps behavior analysts predict and interpret how people allocate their time, effort, and responses across various activities or behaviors.

The matching law can be especially useful in understanding choices made in everyday situations, where behavior is influenced by competing sources of reinforcement.

Key Components of the Matching Law

1. Response Allocation: Refers to how an individual distributes their behavior across available options. For example, a child might spend more time playing with a favorite toy than doing homework, depending on the reinforcement available from each activity.

2. Rate of Reinforcement: Refers to how frequently reinforcement is provided for a particular behavior. Higher rates of reinforcement generally attract more responses, as the individual is more motivated to engage in activities that consistently provide rewards.

3. Relative Reinforcement Value: Different types of reinforcement have different values to individuals. The value of each reinforcement influences the choice and distribution of responses. For instance, social praise may be highly reinforcing for some, while tangible rewards (like stickers or toys) may be more motivating for others.

Using the Matching Law to Interpret Response Allocation

1. Example 1: Classroom Behavior Management

• Scenario: A teacher notices that students are frequently talking to one another during independent work time rather than focusing on their assignments.

• Matching Law Interpretation: The teacher realizes that the rate of reinforcement (e.g., social attention) for talking with peers is higher than the reinforcement for completing assignments.

• Intervention: To shift response allocation, the teacher increases the reinforcement rate for on-task behavior by providing verbal praise or tokens when students are focused on their work. As the reinforcement for staying on task increases, students begin to allocate more responses to working on their assignments instead of talking.

2. Example 2: Reducing Screen Time in Children

• Scenario: A parent wants to reduce their child’s screen time and increase engagement in other activities, such as reading or playing outside.

• Matching Law Interpretation: Currently, screen time offers a high rate of reinforcement (e.g., entertainment, bright colors, sounds), while other activities may not provide as immediate or engaging reinforcement.

• Intervention: The parent introduces additional reinforcement for non-screen activities, like providing a small reward for every 30 minutes spent reading or playing outside. As reinforcement for these activities increases, the child starts to allocate more time to them and less time to screen use, aligning their response allocation with the modified reinforcement distribution.

3. Example 3: Understanding Employee Productivity

• Scenario: In a workplace, some employees spend more time on social media during work hours than on work-related tasks.

• Matching Law Interpretation: The employees may find social media more reinforcing (e.g., social interaction, entertainment) compared to work tasks, which offer less immediate or engaging reinforcement.

• Intervention: The employer could introduce reinforcement for work-related behavior, such as bonuses or public recognition for high productivity. By increasing reinforcement for work tasks, employees are more likely to allocate their responses toward productivity rather than social media.

4. Example 4: Addressing Noncompliance in Children with ASD

• Scenario: A BCBA observes that a child with autism often refuses to complete tasks and instead engages in escape-maintained behaviors, such as leaving the instructional area.

• Matching Law Interpretation: The child’s noncompliant behavior is reinforced by the removal of demands (escape), whereas compliance with the tasks offers less immediate or valuable reinforcement.

• Intervention: The BCBA could increase the reinforcement for task compliance by providing preferred items or activities after each task is completed. This increases the rate of reinforcement for compliance, leading the child to allocate more responses to compliant behavior and fewer to escape behaviors.

5. Example 5: Social Skill Development in Group Settings

• Scenario: A BCBA is working with a teenager who often stays on the sidelines during group activities, engaging minimally with peers.

• Matching Law Interpretation: The student may find reinforcement from isolation or solo activities (such as avoiding social anxiety), while interactions with peers offer limited or less predictable reinforcement.

• Intervention: The BCBA could work on building reinforcement for social participation, perhaps through structured games that allow the teen to gradually experience positive reinforcement from social interactions. As the reinforcement for social behavior increases, the teen may start allocating more responses to group activities, resulting in greater engagement with peers.

Summary

The matching law provides a framework for understanding how individuals allocate their responses based on available reinforcement. By assessing how response allocation is influenced by reinforcement rates, BCBAs can design interventions to encourage desired behaviors and reduce undesired ones. Through changes in the frequency, type, and value of reinforcement, practitioners can help individuals shift their response allocation toward behaviors that are more socially significant or beneficial in their environments.

Here are additional real-world scenarios that illustrate how BCBAs can implement the matching law to interpret and influence response allocation:

Scenario 6: Increasing Exercise in Adolescents

Client: Alex, a 14-year-old who prefers playing video games over physical activity. Alex’s parents and BCBA want to encourage him to spend more time on physical activities, like playing basketball or going for a walk, as he currently allocates nearly all of his free time to video games.

Matching Law Interpretation: Video games provide a high rate of reinforcement (entertainment, achievement, social interaction with friends online) compared to physical activities, which may currently offer less immediate or compelling reinforcement.

Intervention: The BCBA collaborates with Alex’s parents to increase reinforcement for engaging in physical activities. For example, each time Alex participates in 30 minutes of physical activity, he earns a token that can be exchanged for extra game time or another reward. By increasing the rate and value of reinforcement for exercise, Alex begins to allocate more of his time to physical activities, shifting his response allocation away from exclusive focus on video games.

Scenario 7: Improving Participation in Group Therapy Sessions

Client: Jamie, a 10-year-old who participates in group therapy sessions but often avoids engaging in activities, preferring instead to play with toys on the sidelines.

Matching Law Interpretation: Playing with toys provides a high rate of reinforcement for Jamie, while group activities offer less immediate or meaningful reinforcement from his perspective.

Intervention: The BCBA arranges the group session so that Jamie can earn preferred rewards (like a sticker or small toy) by participating in group activities. Additionally, the BCBA introduces more engaging activities within the group, like games or songs Jamie enjoys, increasing the reinforcement value of group participation. As a result, Jamie’s response allocation shifts, and he begins to engage more consistently in group activities.

Scenario 8: Reducing Excessive Hand-Raising in the Classroom

Client: A teacher is working with Sarah, a 9-year-old student who frequently raises her hand, often disrupting the flow of class. The teacher wants to encourage Sarah to reserve hand-raising for more relevant or challenging questions.

Matching Law Interpretation: Sarah receives reinforcement (e.g., teacher attention) each time she raises her hand, regardless of whether her contributions are relevant. This high rate of reinforcement for hand-raising drives a high rate of response allocation to this behavior.

Intervention: The BCBA works with the teacher to create a plan where Sarah earns reinforcement for hand-raising only when her questions or contributions are related to the lesson topic. Additionally, Sarah can earn a token at the end of class if she raises her hand a reasonable number of times. This intervention reduces the rate of reinforcement for irrelevant hand-raising while reinforcing more appropriate contributions, leading Sarah to allocate her responses more selectively.

Scenario 9: Balancing Social Interaction and Independent Work in Adults with Disabilities

Client: A group of adults with developmental disabilities in a supported work program. Many of the clients prefer engaging in social interactions with peers rather than focusing on assigned work tasks.

Matching Law Interpretation: Social interactions provide a high rate of reinforcement (e.g., immediate social feedback) compared to the work tasks, which offer less immediate reinforcement.

Intervention: The BCBA collaborates with job coaches to increase reinforcement for work tasks, such as providing a token for each task completed that can be exchanged for a preferred activity during breaks. By raising the reinforcement for completing work tasks, the clients begin to allocate more time to their tasks rather than socializing, achieving a better balance between work and social interaction.

Scenario 10: Decreasing Off-Task Behavior During Homework Time

Client: Miguel, an 11-year-old who frequently gets distracted during homework time by playing with nearby toys, resulting in minimal homework completion.

Matching Law Interpretation: Playing with toys offers more immediate reinforcement (fun, sensory stimulation) than completing homework tasks, leading Miguel to allocate more responses to playing than to homework.

Intervention: The BCBA and Miguel’s parents implement a system where Miguel earns a token for each completed homework question, which he can exchange for a brief play break with his toys. Additionally, once all homework is completed, Miguel can engage in a longer play session. By increasing reinforcement for homework completion and delaying toy play, Miguel begins to allocate more responses to completing his homework, gradually reducing his off-task behavior.

Scenario 11: Encouraging Functional Communication Over Problem Behavior

Client: Leo, a 6-year-old boy with developmental delays who engages in disruptive behavior (e.g., crying, hitting) to get attention from adults. His BCBA wants to encourage functional communication, like saying “Help me,” as an alternative to disruptive behavior.

Matching Law Interpretation: Currently, disruptive behaviors receive a high rate of reinforcement (attention from adults), whereas functional communication has a lower rate of reinforcement, leading Leo to allocate more responses toward disruptive behaviors.

Intervention: The BCBA and caregivers increase reinforcement for functional communication by immediately attending to Leo when he says “Help me” and ignoring (or minimally responding to) his disruptive behavior. Over time, the increased reinforcement for functional communication encourages Leo to allocate more responses to asking for help instead of engaging in disruptive behavior.

Scenario 12: Reducing Tantrums During Mealtime Transitions

Client: Bella, a 4-year-old with autism, often has tantrums when it’s time to transition from playtime to mealtime. Her BCBA is tasked with helping her transition smoothly to mealtime without tantrums.

Matching Law Interpretation: Playing offers immediate, high-value reinforcement for Bella, while mealtime provides less immediate reinforcement, making her more likely to allocate responses to continuing play and resisting transition.

Intervention: The BCBA introduces a plan where Bella earns a preferred item or reward for smoothly transitioning to mealtime. For example, if she transitions without a tantrum, she receives a preferred food item at the start of the meal or gets to play with a favorite toy for a short time afterward. By increasing the reinforcement for transitioning, Bella begins to allocate more responses toward transitioning smoothly and fewer toward resisting mealtime.

Summary

In each of these scenarios, the matching law helps BCBAs interpret how clients allocate their responses based on reinforcement rates. By adjusting the rate and value of reinforcement associated with desired behaviors, BCBAs can shift response allocation, promoting socially appropriate and beneficial behaviors. The matching law provides a valuable framework for understanding and influencing choices across various settings and individuals.

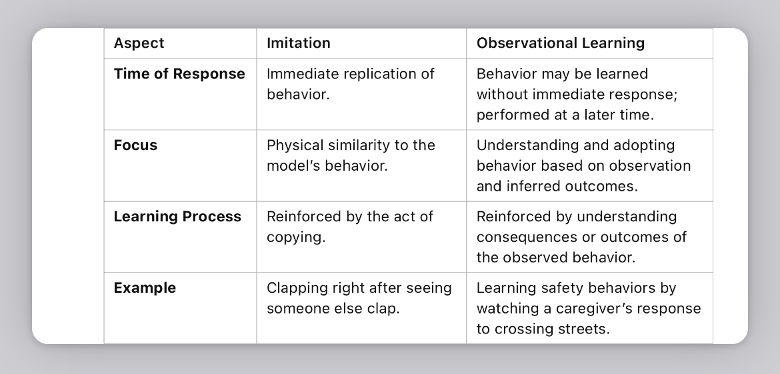

B.24. Identify and distinguish between imitation and observational learning

Understanding Imitation and Observational Learning

In behavior analysis, both imitation and observational learning are important processes by which individuals acquire new skills or behaviors. However, they have distinct features that set them apart.

Imitation

• Definition: Imitation occurs when an individual replicates the actions or behaviors of another person (referred to as a model) immediately after observing them.

• Key Components:

Physical Similarity: The action of the imitator closely resembles that of the model.

Temporal Contiguity: The behavior occurs right after seeing the model, emphasizing a close time relationship.

Function of Behavior: The act itself is reinforced, not necessarily the understanding of its purpose.

• Examples:

A child claps their hands right after seeing their parent do it.

• A toddler sticks out their tongue in response to someone else doing the same.

Observational Learning

• Definition: Observational learning involves acquiring new behaviors or modifying existing ones by observing others, without the need for immediate imitation.

• Key Components:

Learning Through Observation: Unlike imitation, the learner does not need to replicate the behavior right away.Understanding of Outcome: Observational learning often includes awareness of the consequences observed in the model, which influences the learner’s future behavior.

• No Immediate Response Needed: The learned behavior may not be demonstrated until a later time.

Examples:

• A student watches a teacher perform a science experiment and later replicates it independently.

• A teenager learns the steps to a dance by observing an online video and practices them later.

Key Differences Between Imitation and Observational Learning

Applications in Behavior Analysis

• Imitation is often used to teach early learners in skill-building and developmental interventions, particularly in structured environments (e.g., a therapist modeling hand-washing).

• Observational Learning is key in social settings and complex tasks, where individuals observe, process, and later apply behaviors they’ve seen in others (e.g., group learning in classrooms).

By identifying and distinguishing between imitation and observational learning, practitioners can tailor interventions to optimize learning and skill acquisition based on the individual needs of the learner.

Here’s a real-world scenario illustrating how a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) might implement imitation and observational learning techniques to help a child with autism develop social and communication skills in a classroom setting:

Scenario: Enhancing Social and Communication Skills Through Imitation and Observational Learning

Setting:

A mainstream kindergarten classroom where a child, Liam, who has autism, is working on developing social and communication skills to better interact with peers.

Goal:

To increase Liam’s ability to join play activities, communicate needs, and respond to social cues from classmates.

Step 1: Baseline Assessment

• The BCBA observes Liam in the classroom to assess his current level of social interaction, communication skills, and imitation abilities.

• Liam shows limited engagement with peers and often plays alone, sometimes observing his classmates but rarely joining them. He occasionally echoes words but struggles with spontaneous communication.

Step 2: Implementing Imitation Training

• Direct Imitation Exercises: The BCBA sets up structured imitation exercises, initially in a one-on-one setting. Using a peer model (a classmate who is receptive and friendly towards Liam), the BCBA guides Liam to imitate simple actions:

• Examples: Clapping hands, waving, and simple greetings.

• Reinforcement: Each time Liam successfully imitates his peer, he is provided with a reward, such as verbal praise or a small preferred item, to reinforce the imitation behavior.

• Goal: To strengthen Liam’s ability to directly imitate peers in real time, laying a foundation for more complex social behaviors.

Step 3: Promoting Observational Learning in Natural Settings

• Peer Observation: The BCBA arranges group activities where Liam can observe peers engaging in play activities, such as building with blocks or drawing.

• The BCBA instructs the peer model to take turns, share materials, and communicate in simple language.

• Delayed Participation: After observing the activity, Liam is encouraged to join in with prompts from the BCBA. For example, the BCBA might say, “Liam, can you ask to take a turn with the blocks?”

• Positive Consequences: The BCBA ensures that Liam receives positive feedback from peers and teachers for participating, reinforcing the behavior he observed.

Step 4: Embedding Social Cues and Generalization

• The BCBA gradually reduces prompts, encouraging Liam to observe and join activities independently.

• Natural Consequences: By observing peers and seeing the positive outcomes of sharing and taking turns, Liam learns that he can gain social interaction and positive reinforcement naturally through these behaviors.

• Generalization Practice: The BCBA collaborates with the classroom teacher to incorporate imitation and observational learning goals throughout the day, ensuring that Liam has multiple opportunities to practice.

Step 5: Monitoring and Adjusting the Intervention

• The BCBA continues to collect data on Liam’s social interactions, communication, and ability to imitate and learn through observation.

• If Liam demonstrates progress, the BCBA may gradually introduce more complex social scenarios or fade support to increase independence.

• If challenges arise, the BCBA adjusts prompts, reinforcement schedules, or peer models as needed.

Outcome

Through structured imitation and observational learning, Liam gradually learns to join group activities, communicate with peers, and respond to social cues. These skills allow him to integrate more fully with his classmates, enhancing his social development and communication abilities in a natural, reinforcing environment.