Here’s a real-world scenario where a BCBA might determine when to implement both stimulus generalization and response generalization to help a client develop adaptive behaviors.

Scenario: Teaching a Child with Autism to Greet Others Appropriately

Background: A child with autism has learned to say “hello” to the BCBA during sessions. The goal is for the child to generalize this greeting behavior to different people and contexts, as well as to expand the range of appropriate greetings they can use.

Stimulus Generalization: Expanding the Greeting to Different People and Settings

Objective: The BCBA wants the child to greet not only the BCBA but also other people in various situations, such as classmates, family members, and teachers.

Steps to Implement:

1. Introduce New People: Gradually, the BCBA introduces other staff members, such as classroom aides or therapists, into the session. The BCBA encourages the child to say “hello” to each new person.

2. Practice in Different Settings: After consistent success in the therapy setting, the BCBA may arrange for greetings to occur in the classroom, playground, and other familiar areas.

3. Reinforce Generalization: Each time the child greets someone new or greets people in new settings, they receive reinforcement (such as praise, a high-five, or a small reward).

Outcome: Through stimulus generalization, the child learns to apply the greeting behavior in various settings and with different people. They no longer greet only the BCBA but generalize the behavior to other individuals in different contexts.

Response Generalization: Expanding the Variety of Greetings

Objective: The BCBA also wants the child to use different forms of greeting beyond saying “hello” to accommodate different social contexts (e.g., saying “hi” to friends, “good morning” to teachers, or “hey” with peers).

Steps to Implement:

1. Model and Prompt Alternative Greetings: The BCBA introduces other common greetings, such as “hi,” “hey,” and “good morning,” and models how to use them based on the context. The BCBA prompts the child to use these different greetings with various people.

2. Reinforce Variability: Whenever the child uses a new greeting appropriately, the BCBA provides reinforcement, helping to encourage the use of multiple greetings.

3. Role-Playing and Practice: The BCBA engages in role-playing scenarios, such as pretend play where the child uses different greetings with “classmates,” “teachers,” or “friends.” This practice helps the child understand when to use different responses.

Outcome: Through response generalization, the child learns to use a range of greetings, making their social interactions more flexible and appropriate for different situations.

Summary

In this scenario, the BCBA uses:

• Stimulus generalization to help the child greet various people in different settings.

• Response generalization to teach the child to use a variety of greetings based on the social context.

This approach helps the child not only broaden where and with whom they greet others but also increase the adaptability and appropriateness of their responses, enhancing social engagement and independence.

Here are examples for both stimulus generalization and response generalization to help clarify each type:

Stimulus Generalization Examples

1. Greeting Others: A child learns to say “hello” to their BCBA in a therapy session. Later, they start saying “hello” to their teacher, classmates, and family members in different environments, such as school, home, or the playground.

2. Washing Hands: A student is taught to wash their hands after using the restroom at school. Over time, they start washing their hands after using the restroom in other places, like home, restaurants, or public restrooms.

3. Responding to Name: A child learns to respond to their name when their parents call them. Eventually, they begin responding when teachers or friends call their name in different settings, like at school, in the park, or at a friend’s house.

4. Following Instructions: A child is taught to follow the instruction “sit down” from their teacher in the classroom. Later, the child follows the same instruction when given by other adults, like parents, therapists, or caregivers, across various environments.

Response Generalization Examples

1. Greeting Others: A child learns to greet others by saying “hello.” Later, they start using different greetings like “hi,” “hey,” and “good morning” depending on the situation and the person they’re addressing, even though they were initially only taught to say “hello.”

2. Requesting Help: A student is taught to raise their hand when they need help in class. Later, the student starts using other ways to ask for help, such as saying “excuse me,” approaching the teacher directly, or using visual cue cards if they are non-verbal.

3. Expressing Emotions: A child learns to express excitement by clapping their hands. Over time, they begin to show excitement in other ways, such as jumping, saying “yay,” or giving a high-five.

4. Sharing with Peers: A child is taught to share toys by handing them to a peer. Later, they expand their sharing behavior by taking turns, inviting others to join their play, or offering different types of toys, even though they were only directly taught the hand-over method.

These examples illustrate how stimulus generalization allows a behavior to extend to new contexts or people, while response generalization enables a range of functionally similar behaviors in response to the same stimulus or situation.

B.15. Identify examples of response maintenance.

Response maintenance refers to the continued occurrence of a behavior over time, even after formal intervention or reinforcement has ended. This is essential in behavior analysis, as it shows that a skill or behavior has become integrated into the individual’s routine and can be maintained without ongoing external support. Here are some examples of response maintenance:

1. Daily Exercise Routine: A client initially learns to exercise regularly through a structured program with a personal trainer. After the program ends, the client continues their exercise routine independently because they’ve developed a habit and enjoy the health benefits.

2. Social Greetings: A child with autism is taught to greet peers with a wave or “hello” at the start of each day in school. Even after the therapist no longer directly reinforces the behavior, the child continues to greet others daily, showing maintenance of the learned social skill.

3. Studying Skills: A student is taught effective study strategies, such as summarizing and reviewing notes nightly. After receiving reinforcement for using these strategies, the student continues to study independently, showing response maintenance of this effective learning behavior.

4. Hand Washing: A young child is taught to wash their hands after using the restroom, with reminders and reinforcement from a caregiver. After the intervention, the child consistently washes their hands on their own, maintaining the habit.

5. Using a Communication Device: A non-verbal individual is taught to request items using a communication device. Initially, they are reinforced with access to the requested item each time they use the device correctly. Over time, the person continues to use the device independently to request items, even without reinforcement every time, showing response maintenance.

6. Following Safety Rules: A child is taught to look both ways before crossing the street through reinforcement and modeling. Later, the child consistently looks both ways before crossing the street, even when not directly reminded or reinforced, demonstrating that this safety skill has been maintained.

7. On-Task Behavior in Class: A student who was previously off-task is taught to stay focused during class, reinforced with praise and rewards. After the intervention ends, the student continues to remain on-task without needing additional reinforcement, showing response maintenance of this productive classroom behavior.

These examples highlight how response maintenance ensures that learned behaviors persist over time, allowing individuals to maintain functional, adaptive skills even after formal support or reinforcement is withdrawn.

NOTE: A BCBA can evaluate the maintenance of a skill by assessing whether the behavior or skill persists over time without ongoing intervention or reinforcement. Here are some methods a BCBA might use:

1. Follow-Up Observations: The BCBA schedules follow-up observations at intervals (e.g., one month, three months, or six months after intervention) to see if the skill continues without reinforcement. They observe in natural settings, such as at home or school, to ensure the skill is being used in the intended context.

2. Data Collection Over Time: Collecting data on the skill across different time points helps track its maintenance. The BCBA can compare this data with the baseline (before intervention) and post-intervention data to determine if the skill has been maintained.

3. Parent or Teacher Reports: For children, the BCBA may gather information from parents, teachers, or other caregivers through interviews or questionnaires. These individuals can report whether the child continues to use the skill in relevant settings and identify any changes over time.

4. Self-Monitoring by the Client: If appropriate, the client can self-monitor and record when they use the skill independently. The BCBA can review these self-reports to assess maintenance, particularly for older clients or adults who can reliably track their own behavior.

5. Natural Reinforcement Checks: The BCBA may check if natural reinforcers (like social praise from peers or benefits of the skill itself) are helping maintain the behavior. Observing that the skill is naturally reinforced can indicate that it will likely continue over time.

6. Probe Trials Without Reinforcement: The BCBA can conduct periodic probe trials where they observe whether the behavior occurs without reinforcement or prompts. This helps determine if the behavior has become part of the client’s regular repertoire and doesn’t require external reinforcement.

7. Generalization Checks: Ensuring the skill generalizes across settings, people, and situations can support maintenance. If the behavior is generalized to various contexts, it is more likely to be maintained independently. The BCBA assesses if the skill is used consistently outside of the training environment.

8. Assessing Fluency and Independence: Skills that are fluent and performed independently without hesitation or need for prompts are more likely to be maintained. The BCBA evaluates how smoothly and independently the client performs the skill as an indicator of maintenance.

Using these methods, BCBAs can systematically evaluate whether the skill is maintained over time, ensuring that the client can use it independently and in real-world settings without continuous support.

B.16. Identify examples of motivating operations.

Motivating operations (MOs) are environmental events or conditions that temporarily alter the effectiveness of a reinforcer or punisher and influence the likelihood of a behavior occurring. MOs are divided into two types: Establishing Operations (EOs), which increase the value of a reinforcer, and Abolishing Operations (AOs), which decrease the value of a reinforcer. Here are examples of each type:

Establishing Operations (EOs): Increase the Effectiveness of a Reinforcer

1. Hunger: When a person hasn’t eaten for several hours, food becomes a more powerful reinforcer. This increase in hunger (EO) makes behaviors like seeking out food or asking for a snack more likely.

2. Thirst: On a hot day or after physical activity, thirst increases, making water or drinks a stronger reinforcer. This thirst (EO) leads to an increased likelihood of drinking behavior.

3. Sleep Deprivation: A person who has not slept well for several nights will value rest and sleep more. This EO increases the likelihood of taking a nap or going to bed early.

4. Attention Deprivation: If a child has received little attention throughout the day, attention from others becomes more reinforcing. This EO might lead the child to engage in behaviors, such as asking questions or showing others their toys, to gain attention.

5. Pain or Discomfort: When someone is in pain, relief from that pain becomes a stronger reinforcer. For example, an EO of pain may lead a person to take medication, lie down, or seek comfort.

Abolishing Operations (AOs): Decrease the Effectiveness of a Reinforcer

1. Satiation: After a large meal, food is less reinforcing, and behaviors related to eating are less likely to occur. Satiation serves as an AO, decreasing the value of food as a reinforcer.

2. Quenching Thirst: After drinking enough water, the individual’s thirst is reduced, making additional drinks less reinforcing. This AO decreases the likelihood of drinking behavior until thirst returns.

3. Social Satiation: If a person has been in a highly social environment all day, the value of social attention might decrease. This AO could make them less likely to seek social interaction and more likely to seek alone time.

4. Pain Relief: After taking medication that alleviates pain, the motivation to find additional pain relief is reduced. This AO decreases the likelihood of seeking further treatment for the pain until it returns.

5. Exercise Fatigue: After intense physical activity, the individual may be less motivated to engage in additional exercise. This fatigue (AO) reduces the reinforcing value of exercise for a period.

Summary

• Establishing Operations (EOs) temporarily increase the value of a reinforcer and make related behaviors more likely.

• Abolishing Operations (AOs) temporarily decrease the value of a reinforcer and make related behaviors less likely.

By understanding and identifying MOs, behavior analysts can predict and influence the likelihood of specific behaviors, which is essential in designing effective interventions.

Understanding and identifying motivating operations (MOs) is crucial for BCBAs because MOs play a significant role in influencing behavior. Here are several reasons why MOs are helpful:

1. Predicting Behavior: MOs help BCBAs predict when a particular behavior is likely to occur. For example, knowing that a child is more likely to seek attention when they’ve had little interaction throughout the day allows the BCBA to prepare and potentially address the behavior proactively.

2. Enhancing Reinforcement Effectiveness: By manipulating MOs, BCBAs can increase the effectiveness of reinforcers during skill acquisition or behavior change programs. For example, if a child is more motivated by food when hungry, the BCBA can schedule teaching sessions before snack time to leverage that motivation.

3. Reducing Problem Behaviors: Understanding MOs helps BCBAs identify the underlying motivations for challenging behaviors. For instance, if a child’s aggressive behavior is driven by attention-seeking due to an EO for attention, the BCBA can work on providing attention through appropriate behaviors instead, reducing the problem behavior.

4. Designing Function-Based Interventions: MOs help BCBAs create interventions that directly address the needs or motivations behind behaviors, leading to more effective and individualized treatment plans. For example, if escape from a task is a strong reinforcer due to an EO (task difficulty or fatigue), the BCBA can modify the task or teach an appropriate way to request breaks.

5. Promoting Generalization and Maintenance: By understanding and using MOs, BCBAs can help ensure that learned behaviors are used in real-world settings. For instance, if a client learns to ask for water during times of thirst, that skill is more likely to generalize and be maintained over time because the motivation is naturally occurring.

6. Preventing Behavioral Extinction: If a behavior is no longer being reinforced, understanding MOs can help BCBAs address times when motivation to engage in the behavior is low. By creating conditions where reinforcement is more valuable (e.g., increasing the EO for a reinforcer), BCBAs can maintain desirable behaviors and prevent them from fading.

7. Improving Quality of Life: MOs allow BCBAs to address basic needs, preferences, and motivations for clients, making interventions more relevant and beneficial. By using MOs, BCBAs can help clients gain access to preferred items, activities, or interactions, improving overall quality of life.

In sum, MOs are a powerful tool for BCBAs, enabling them to better understand, predict, and influence behavior by considering the current motivations and environmental factors that affect clients’ behavior. This leads to more targeted, effective, and compassionate behavior interventions.

Here are some real-world scenarios in which a BCBA might use motivating operations (MOs) to influence behavior effectively:

Scenario 1: Using Hunger as an Establishing Operation for Learning New Skills

Background: A BCBA is working with a child on communication skills, specifically requesting preferred snacks. The child has shown little interest in using communication devices during sessions.

Strategy Using MO: The BCBA schedules the session right before the child’s typical snack time, creating an Establishing Operation (EO) for hunger, which increases the value of snacks as a reinforcer. During the session, the BCBA prompts the child to use the communication device to request snacks and reinforces successful requests by giving the child small portions.

Outcome: Because hunger increases the child’s motivation to ask for snacks, they are more likely to engage with the communication device, leading to faster acquisition of the requesting skill.

Scenario 2: Attention as an Establishing Operation to Reduce Disruptive Behavior

Background: A student frequently disrupts the classroom by calling out for attention. The BCBA observes that these disruptions increase after long periods without social interaction.

Strategy Using MO: The BCBA implements a structured schedule for positive attention, such as giving the child brief, planned moments of positive attention every 10 minutes. This serves as an Abolishing Operation (AO), reducing the child’s need to call out for attention by providing it more frequently on a consistent schedule.

Outcome: The child’s disruptive behavior decreases, as their need for attention is now being met proactively, reducing the motivation to seek it through inappropriate behaviors.

Scenario 3: Using Thirst as an Establishing Operation for Self-Advocacy Skills

Background: A young adult with autism is learning to request drinks appropriately. The BCBA finds that the client is generally indifferent to practicing this skill unless they are particularly thirsty.

Strategy Using MO: The BCBA schedules the session right after the client has completed an exercise routine, creating an EO for thirst. During the session, the BCBA reinforces the client’s requests for water, helping them learn to advocate for their needs in natural contexts.

Outcome: The client becomes more motivated to practice requesting drinks when they are thirsty, leading to better generalization of the skill.

Scenario 4: Using Task Difficulty as an Establishing Operation to Teach Requesting Breaks

Background: A student often tries to escape challenging academic tasks by exhibiting disruptive behavior. The BCBA suspects the behavior is maintained by escaping difficult tasks.

Strategy Using MO: The BCBA introduces progressively more challenging tasks and teaches the student how to appropriately request a break. By gradually increasing task difficulty, the BCBA creates an EO for break requests, as the student is motivated to avoid overly difficult tasks. Each time the student requests a break appropriately, they are given a short break, reinforcing this more adaptive response.

Outcome: The student learns to ask for breaks instead of engaging in disruptive behavior, effectively using an adaptive skill that addresses the motivation to escape difficult tasks.

Scenario 5: Using Satiation as an Abolishing Operation for Reducing Food-Seeking Behavior

Background: A client exhibits frequent food-seeking behavior, such as going to the kitchen and asking for snacks multiple times during the day. This behavior is sometimes inappropriate or disruptive.

Strategy Using MO: The BCBA introduces a schedule where the client has frequent small snacks at predictable times, helping to ensure they are less likely to experience extreme hunger. This acts as an AO by reducing the motivation to seek food outside of these scheduled times.

Outcome: With consistent access to food and reduced hunger, the client’s food-seeking behavior decreases, allowing them to focus on other activities.

Scenario 6: Social Interaction as an Establishing Operation for Increasing Social Skills

Background: A child is working on social skills, such as initiating conversation and sharing toys. The BCBA notices that the child is more motivated to interact after spending time alone.

Strategy Using MO: The BCBA sets up social skills training sessions after periods when the child has had limited social interaction. This alone time creates an EO for social engagement, increasing the child’s motivation to participate in social activities when the session begins.

Outcome: The child’s willingness to engage in social skills activities increases, allowing for more effective skill-building.

Summary

These scenarios demonstrate how BCBAs can strategically use motivating operations to enhance learning, reduce problem behaviors, and improve adaptive skills by leveraging the client’s natural motivations. By understanding and manipulating MOs, BCBAs can create conditions that make reinforcers more or less effective, leading to better behavioral outcomes.

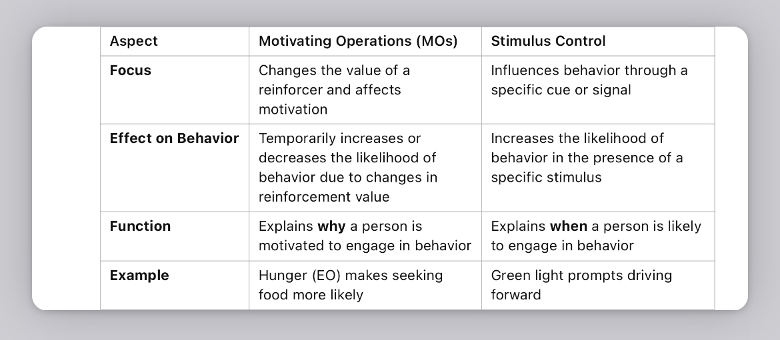

B.17. Distinguish between motivating operations and stimulus control.

Motivating Operations (MOs) and Stimulus Control are both important concepts in behavior analysis, but they serve different functions in influencing behavior. Here’s a breakdown of each concept and the key differences between them:

Motivating Operations (MOs)

Definition: MOs are environmental events or conditions that temporarily affect the value of a reinforcer or punisher and influence the likelihood of a behavior occurring. They change how strongly someone is motivated to engage in a behavior.

Types:

• Establishing Operations (EOs): Increase the effectiveness of a reinforcer, making the behavior more likely (e.g., hunger increases the value of food).

• Abolishing Operations (AOs): Decrease the effectiveness of a reinforcer, making the behavior less likely (e.g., fullness decreases the value of food).

Example: When a child is thirsty, water becomes a more powerful reinforcer (EO), making behaviors like requesting or seeking water more likely. When the child’s thirst is quenched, water loses its reinforcing value (AO), making these behaviors less likely.

Function: MOs affect the “why” of behavior. They explain why a person might be more or less likely to engage in a behavior due to changes in motivation or reinforcement value.

Stimulus Control

Definition: Stimulus control refers to the influence of a specific stimulus (cue or signal) on the likelihood of a behavior, due to a history of reinforcement in the presence of that stimulus. When a behavior occurs more frequently in the presence of a specific stimulus, we say the behavior is under stimulus control.

Example: When a traffic light turns green, drivers are more likely to press the gas pedal because they have learned that green lights are associated with moving forward. Here, the green light exerts stimulus control over the driving behavior.

Function: Stimulus control affects the “when” of behavior. It tells us when a person is more likely to perform a behavior in response to a specific cue or signal.

Key Differences Between Motivating Operations and Stimulus Control

Imagine a child learning to say “please” to request snacks:

• Motivating Operation: The child’s hunger acts as an EO, making the snack a highly desirable reinforcer. This increases the likelihood that the child will use “please” to get the snack because they are motivated by hunger.

• Stimulus Control: When the child sees a parent holding a snack, this visual cue (the sight of the snack) prompts the behavior of saying “please” because the child has learned that the parent often gives them the snack in response to saying “please.”

In this example:

• Hunger (MO) affects how strongly the child wants the snack, making “please” more likely due to increased motivation.

• Parent holding the snack (stimulus control) serves as a cue that signals the opportunity to say “please” to receive the snack.

Summary

• Motivating Operations affect the value of a reinforcer and the motivation to perform a behavior, addressing why someone wants something.

• Stimulus Control involves specific cues that signal the availability of reinforcement, addressing when the behavior is likely to occur.

By understanding the differences between MOs and stimulus control, BCBAs can create more effective interventions by both adjusting the motivation behind behaviors and controlling the cues that trigger them.

Here’s a real-world scenario where a BCBA might use both motivating operations (MOs) and stimulus control to address a child’s disruptive behavior during homework time, implementing different procedures to create an effective intervention.

Scenario: Addressing Homework-Related Disruptive Behavior

Background: A young student frequently engages in disruptive behavior (e.g., yelling, getting up from their seat) during homework time at home. The BCBA is asked to help reduce these behaviors and increase the child’s ability to complete homework independently.

Step 1: Identifying the Motivating Operation (MO)

Through observation, the BCBA identifies that the child’s disruptive behavior often serves as a way to escape from homework tasks. Homework is challenging for the child, which creates an Establishing Operation (EO) for escape. This EO increases the value of avoiding homework, making escape behaviors more likely.

Procedure Using MO:

• The BCBA modifies the difficulty and duration of the homework tasks by breaking assignments into shorter, more manageable segments. This reduces the EO for escape, as the child is now less overwhelmed.

• The BCBA also introduces periodic breaks as reinforcement for completing each short segment, allowing the child to experience natural, scheduled escape, which reduces the overall motivation to engage in disruptive behavior.

Outcome: By reducing the EO for escape, the BCBA decreases the motivation for the child to use disruptive behavior to avoid homework, making it easier to focus on the tasks.

Step 2: Implementing Stimulus Control with Visual Cues and Structure

The BCBA recognizes that the child doesn’t have clear signals or routines that establish when homework time begins, what’s expected, or when it will end. This lack of structure contributes to anxiety and confusion, which can increase disruptive behavior.

Procedure Using Stimulus Control:

• Visual Schedule: The BCBA creates a visual schedule that clearly shows homework time, break times, and an “end of homework” time. This visual cue provides structure and acts as a discriminative stimulus (SD), signaling when to start working and when the session will end.

• Designated Homework Space: The BCBA sets up a specific area for homework that includes all necessary materials. Sitting in this area becomes an SD that signals it’s time to focus on homework. This designated space creates a consistent, predictable routine.

Outcome: The visual schedule and designated workspace help the child understand when homework begins and ends, reducing anxiety and establishing stimulus control over the behavior. The child becomes more likely to start and remain seated during homework time.

Step 3: Reinforcing Desired Behavior (Positive Reinforcement)

The BCBA also implements a reinforcement strategy to encourage appropriate behavior (sitting, working quietly) during homework time.

Procedure Using Positive Reinforcement:

• The BCBA sets up a reinforcement system where the child earns points or tokens for completing each segment of homework without engaging in disruptive behavior. These points can be exchanged for a preferred activity (like playing a game) at the end of homework time.

• Differential Reinforcement of Alternative Behavior (DRA): The BCBA specifically reinforces behaviors that serve as alternatives to disruption, such as raising a hand to ask for help or requesting a break.

Outcome: The positive reinforcement system increases the likelihood of appropriate homework behavior. The reinforcement (tokens and preferred activity) provides motivation, while the structure created by the SDs and MOs reduces disruptive behaviors.

Summary of Procedures Used

1. Addressing Motivating Operations (MOs): Reduced task difficulty and scheduled breaks address the EO for escape, lowering the motivation to engage in disruptive behavior.

2. Establishing Stimulus Control: Visual schedules and designated homework space serve as SDs that guide appropriate behaviors and reduce confusion and anxiety.

3. Positive Reinforcement and Differential Reinforcement: A token system and specific reinforcement of alternative behaviors encourage on-task behavior and reduce disruptions.

Through these combined procedures, the BCBA creates a supportive environment that both reduces the child’s motivation to escape homework (MO) and establishes clear signals for expected behaviors (stimulus control). This integrated approach helps the child develop better focus and independence with homework over time.

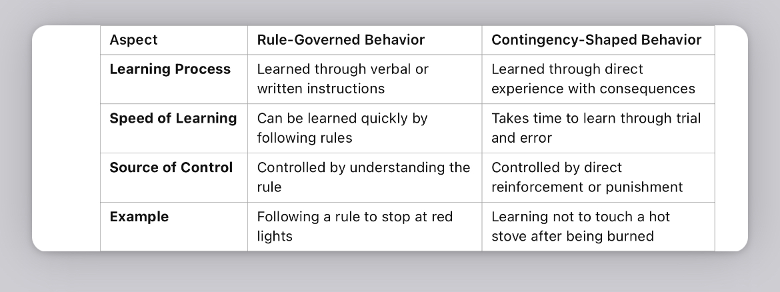

B.18. Identify and distinguish between rule-governed and contingency-shaped behavior.

Rule-Governed Behavior and Contingency-Shaped Behavior are two types of behavior influenced by different learning processes. Here’s an overview of each and how they differ:

Rule-Governed Behavior

Definition: Rule-governed behavior is behavior controlled by a verbal or written rule that describes a contingency (relationship between behavior and consequence). The individual follows the rule based on an understanding of the consequences, even if they haven’t directly experienced them.

Characteristics:

• Based on instructions, rules, or descriptions of contingencies.

• May occur without direct reinforcement or punishment.

• Often quick to learn, as it doesn’t require direct experience with the consequences.

Example:

• A student reads a rule that says, “Turn off cell phones during class.” They follow the rule by turning off their phone, even though they haven’t been directly punished for using their phone in class.

• A person follows traffic laws, such as stopping at a red light, because they understand there’s a consequence for not doing so, even if they haven’t been fined for running a red light.

Usefulness: Rule-governed behavior is helpful in situations where it’s impractical or unsafe to learn through direct experience, such as following safety procedures or understanding social norms.

Contingency-Shaped Behavior

Definition: Contingency-shaped behavior is behavior that is directly shaped by the consequences experienced. This type of behavior is learned through trial and error, with reinforcement or punishment directly affecting the likelihood of future behavior.

Characteristics:

• Requires direct experience with the consequences.

• Often takes longer to learn, as it’s based on repeated exposure to the contingency.

• Behavior may be more sensitive to immediate reinforcement or punishment.

Example:

• A child touches a hot stove and learns not to touch it again because of the direct experience of pain. The behavior of avoiding the stove was shaped by the contingency of touching something hot.

• A person learns that speaking too loudly in a quiet library leads to being shushed by others. Through repeated experiences, they learn to speak softly in that environment.

Usefulness: Contingency-shaped behavior is often more flexible and adaptable because it’s based on direct, real-world experience with consequences, allowing individuals to adjust behavior based on immediate feedback.

Key Differences Between Rule-Governed and Contingency-Shaped Behavior

Imagine teaching a child to avoid touching a hot stove:

• Rule-Governed Behavior: The child is told, “Don’t touch the stove; it’s hot and will hurt you.” They follow this rule to avoid touching the stove, even if they haven’t directly experienced the burn.

• Contingency-Shaped Behavior: If the child ignores the rule and touches the stove, they experience a burn. This direct consequence (pain) shapes their future behavior, making them more likely to avoid touching the stove.

In this example:

• The rule provides verbal information about the potential consequence (pain) and encourages the child to avoid the behavior without direct experience. If the child follows the rule, their behavior is guided by rule-governed learning.

• Direct experience with the consequence (burning their hand) shapes the child’s behavior if they disregard the rule and touch the stove. This trial-and-error experience makes them less likely to touch the stove again due to contingency-shaped behavior.

Summary

• Rule-Governed Behavior: Controlled by verbal or written descriptions of contingencies. The behavior is based on an understanding of the consequences without direct experience (e.g., following traffic laws, safety procedures).

• Contingency-Shaped Behavior: Controlled by the actual experience of reinforcement or punishment. The behavior is learned through direct interaction with the environment (e.g., avoiding touching hot surfaces after being burned).

By distinguishing between rule-governed and contingency-shaped behavior, BCBAs can tailor interventions to suit the individual and the context. For instance, using rules can help teach safety and compliance quickly, while contingency-shaped learning can promote adaptability and natural responses in real-world settings.

Here’s a real-world scenario where a BCBA uses both rule-governed and contingency-shaped behavior strategies to help a child with autism develop appropriate social skills in school.

Scenario: Teaching a Child to Ask for Help Appropriately

Background: A child with autism often engages in disruptive behaviors (e.g., yelling or leaving their seat) when they struggle with tasks in the classroom. The BCBA’s goal is to teach the child to ask for help appropriately when they need assistance.

Step 1: Teaching Rule-Governed Behavior (Initial Instruction)

Strategy: The BCBA introduces a rule to the child: “If you need help, raise your hand and say ‘help, please,’ and someone will come to help you.” The BCBA explains the steps clearly and provides a visual reminder on the child’s desk to reinforce this rule.

Implementation:

• The BCBA teaches the child to follow the rule by practicing the sequence (raising hand and saying “help, please”) in structured sessions.

• During these sessions, the BCBA provides verbal praise and reinforcement (such as tokens or small rewards) whenever the child follows the rule to ask for help, even if they do not initially need assistance.

Outcome: The child begins to understand that following the rule to ask for help will result in assistance, even without experiencing the consequences of yelling or leaving their seat. This rule-governed behavior establishes the foundation for an appropriate way to seek help.

Step 2: Shaping Behavior Through Contingency (Real-Time Classroom Practice)

Once the child understands the rule, the BCBA allows them to practice in the natural classroom environment, where they may experience direct consequences (both positive and negative) related to their behavior.

Strategy: The BCBA gradually reduces prompts and reinforcement for the rule, allowing natural classroom contingencies to shape the behavior. The BCBA ensures the child receives help when they ask appropriately and does not gain teacher attention if they yell or leave their seat.

Implementation:

• Positive Reinforcement for Following the Rule: When the child follows the rule (raising hand and saying “help, please”), the teacher immediately provides help, reinforcing the behavior with real, meaningful assistance.

• Natural Consequences for Disruptive Behavior: If the child reverts to yelling or leaving their seat, the teacher and BCBA agree not to provide attention or assistance until the child returns to their seat and asks appropriately. Over time, this contingency reduces disruptive behaviors, as they do not lead to the desired outcome (help).

Outcome: The child learns, through direct experience, that following the rule results in help and attention, while disruptive behavior does not. This contingency-shaped learning solidifies the child’s ability to ask for help appropriately, even when the visual reminder or verbal rule is no longer present.

Summary of Implementation

1. Rule-Governed Behavior: The BCBA establishes a rule and practices it with the child (“Raise your hand and say ‘help, please’ to get assistance”) to quickly teach the desired behavior.

2. Contingency-Shaped Behavior: In the natural environment, the child’s behavior is shaped by real-life consequences—receiving help when they ask appropriately and not receiving help when they act disruptively.

Through this combination, the BCBA ensures the child learns both the rule and the natural consequences, leading to durable, context-appropriate behavior in the classroom. This approach allows the child to generalize the skill and maintain it over time.